This is High Background Steel, the AI slop division of Summer Lightning. These are experiments in AI writing with the conceptual process listed at the bottom. You can opt out of this section jf its not your vibe.

I’ve worn the Man-tle S3 R15 jacket for two fall/winters now. It is a simple black jacket with a large silver zipper that is appropriately described as “hardware” on the Man-tle site. When it was new, it was slightly awkward to wear. Every time I wore it felt like stepping into a mech suit. But over time, it has acquired some patina ,wear and memory. Now it sits well on my body, and I can almost sense the places this jacket has been. Some time last fall, while wearing this jacket on a stroll in Tokyo, the phrase “clothes as architecture” got stuck in my head and has become a motif I reach for when looking at, and enjoying clothes.

The following is an essay based on a conversation I had with chatGPT O3 mini about clothes as architecture, spanning over 4 weeks.

Man-tle and the Spirit of Bauhaus

The S3 Man-tle jacket, with its sturdy waxed cotton and commanding silver zipper, embodies the essence of Bauhaus architecture. Its unassuming silhouette speaks to the movement’s credo of “form follows function,” where nothing exists merely for ornamentation. The waxed cotton recalls the honest materials of Bauhaus buildings—exposed steel, glass curtain walls, and unadorned concrete—that wear beautifully over time, acquiring a patina of use and memory. The oversized silver zipper acts as an industrial accent, like the steel supports in a Gropius façade: simple, robust, and elevating the design through precise details.

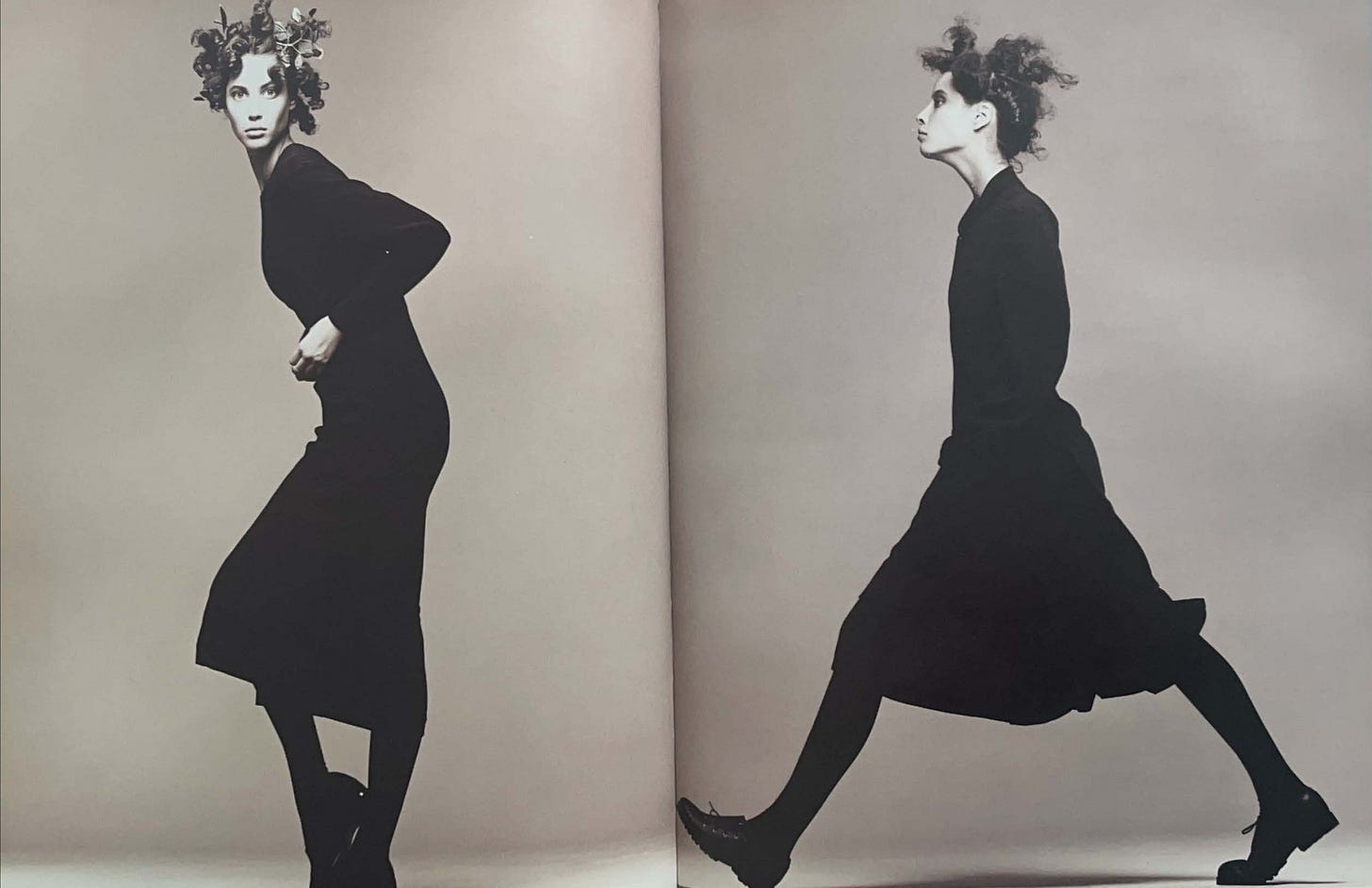

Bauhaus’s emphasis on functional simplicity and industrial detail influenced fashion designers like Rei Kawakubo, whose 1981 Comme des Garcons show would reframe how garments could be conceived as sculptural forms. Notably, the founders of Man-tle, Aida Kim and Larz, worked under Kawakubo at Comme des Garçons before spinning off to establish their own label, presumably inheriting her experimental ethos.

Rei Kawakubo’s Bauhaus Influence

In 1981, Rei Kawakubo debuted her first Paris collection for Comme des Garçons, challenging conventions with deconstructed silhouettes and an emphasis on raw form. Kawakubo’s work, even though criticized by French critics at the time, resonated with the Bauhaus ethos: she treated garments as three-dimensional structures, exploring negative space and material honesty. Her muted palette and sculptural shapes echoed the austere facades of Masters’ Houses in Dessau, and several writers have pointed to her drawing inspiration from the works of László Moholy-Nagy. Rei Kawakubo also famously detested being pigeonholed as a “fashion designer”, a position reminiscent of the Bauhaus philosophy of Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art. The Man-tle jacket, when viewed through this lens, becomes a modern heir to Kawakubo’s vision— combining industrial detail with sculptural simplicity.

Bauhaus in the grain

Though the overt references to Bauhaus—primary colors, rectilinear forms, steel tubing—have been exhaustively explored, the movement’s underlying principles endure in pieces like the Man-tle jacket. Contemporary designers may no longer cite Gropius or Moholy-Nagy by name, yet their insistence on functionalism, material integrity, and the fusion of art with everyday life persists. This jacket, softened by wear yet unwavering in its structure, carries forward Bauhaus belief that well-designed objects should adapt to their users, becoming more personal and more indispensable with time.

A response to the Second Industrial Revolution

Both the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism emerged as creative responses to the upheavals of the Second Industrial Revolution (circa 1870–1914). Mass production, electrification, and new building technologies—steel framing, reinforced concrete, plate glass—upended traditional craft and architecture. During the earlier years, in Britain, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement championed a return to handcrafted integrity, reacting against mechanized ornamentation and advocating for the social value of labor. This emphasis on material honesty and human-scale craftsmanship finds a parallel today in the backlash against AI-generated text, where calls for authenticity and the “human touch” echo Morris’s rallying cry.

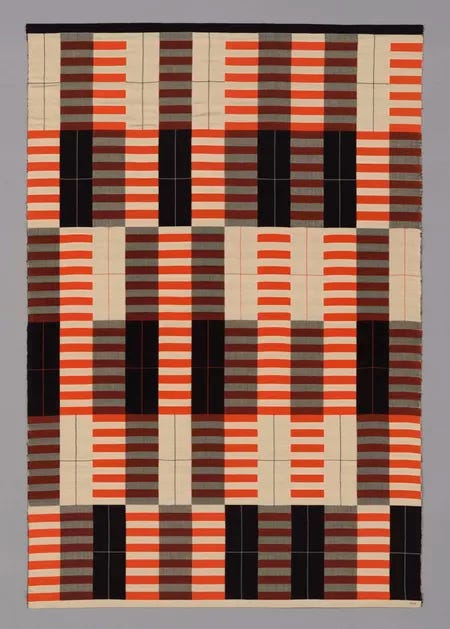

Building on Morris’s dedication to craftsmanship, but fraying in a crucial aspect, Bauhaus pioneers embraced industrial processes—steel framing, glass curtain walls, and mechanized looms—to translate the warmth of handwork into scalable design. This paradoxical fusion of artisanal integrity with machine‑age efficiency created a productive tension, embodying Marshall McLuhan’s idea that art can anticipate the cultural trauma of emerging technologies, revealing both their promise and their perils before society fully grasps them.

With Bauhaus, Walter Gropius envisioned a synthesis: the tactile warmth of Morris’s handwoven textiles alongside the possibilities of machine-made precision. Workshops in weaving, metalwork, and cabinetry sat alongside courses in architecture and industrial design. Students experimented directly with steel tubing, glass curtain walls, and reinforced concrete—materials emblematic of the modern age—designing prototype furniture and building elements intended for mass production. Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, crafted from bent tubular steel, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, with its expansive glass and steel planes, exemplified the movement’s commitment to material honesty and industrial fabrication methods. Bauhaus furniture—tubular-steel chairs, cantilevered tables—demonstrated that industrial techniques could yield elegant, functional forms. Russian Constructivists similarly celebrated machinery as an aesthetic force, producing posters, pavilions, and sculptures that foregrounded steel and glass as symbols of progress.

Artistic techniques as ‘high’ background steel

Analogous to how all modern steel carries faint traces of nuclear fallout—rendering only pre-1940s steel truly “low background”—the diffusion of new technologies leaves an indelible imprint on creative practice. When artists first engage emerging tools or paradigms, they foreground process and material: the Bauhaus celebrated industrial methods alongside handcraft, John Cage’s indeterminate music highlighted the unpredictability of chance operations, and the Oulipo writers imposed formal constraints to reveal the mechanics of composition. Over time, however, these techniques become absorbed into the aesthetic mainstream and taken for granted—almost like the artistic movements are traversing the five stages of grief: denial and anger (the Arts and Crafts movement under William Morris), bargaining (Art Nouveau’s attempt to reconcile mechanization with organic ornament), depression (the Dadaists’ nihilistic rejection of technological rationality), and finally acceptance and integration (the Bauhaus synthesis of craft and industry).

Writers today confront a similar dilemma as AI-generated text proliferates. Does machine-assisted prose carry the same depth of human expression? Must we retreat to pen and parchment to preserve authenticity? Bauhaus foregrounds a continuous becoming, allowing new processes to flow through the creative assemblage—enfolding and reconfiguring practice from within rather than casting them aside. Future discourse may focus on transparency of method—outlining the proportion of human writing, the prompts that guided AI responses, and the passages refined through human revision. In this way, each piece of writing could include a provenance note: a concise recipe that maps its blended human‑machine origins.

The enduring appeal of Bauhaus stems from its deliberate engagement with the tension between craft and machine. As Walter Gropius proclaimed in his 1923 manifesto “Art and Technology – A New Unity,” the school sought to harmonize artisanal traditions with industrial processes, forging objects that were simultaneously warm and mechanized. Gropius underscored this unity, stating, “Technology does not need art, but art does need technology”.

Conceptual process for the essay:

Initial Prompt: "Clothes as Architecture"

Starting idea: explore clothing as a form of built structure.

You described the Mant-le jacket with this framework in mind.

Architectural Association: Bauhaus

Based on your description, I suggested the Bauhaus movement as a relevant architectural and design reference.

You examined Bauhaus buildings, particularly the Fagus Factory by Walter Gropius, and noticed resonances with the form and feel of the jacket.

Fashion Designers Inspired by Bauhaus

Prompted for fashion designers influenced by Bauhaus principles.

Two major names emerged:

Yves Saint Laurent, specifically the 1965 Mondrian Collection, which is a direct visual borrowing of Bauhaus/De Stijl motifs.

Rei Kawakubo (Comme des Garçons), whose work interprets Bauhaus principles on a deeper, more structural and material level.

Surface vs. Structural Inspiration

You compared:

YSL’s Mondrian dresses: seen as a literal, graphic translation—"copy-paste" Bauhaus.

Kawakubo’s work: as a philosophical and constructional translation—focusing on materiality, form, and process.

This became a key insight: true Bauhaus inspiration is not just visual but methodological.

Brand Connection: Man-tle’s Lineage

Discovery: Aida Kim and Larz, founders of Mantle, both previously worked at Comme des Garçons.

Aha moment: this helps explain the layered transmission of Bauhaus ideas—filtered through Kawakubo's interpretation and absorbed into Mantle’s design language.

Historical Context: Bauhaus vs. Previous Movements

Comparison with prior design movements:

Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts (William Morris): anti-industrial, emphasizing handcraft and natural forms.

Bauhaus: synthesized industrial production and craftsmanship—embraced technology as a design tool, not a threat.

This clarified why Bauhaus has such lasting relevance: it embraces contradictions and builds bridges between opposites.

Deeper Theme: Technology and Artistic Process

Observation: when art meets technology, the process becomes visible and vital.

Over time, as movements mature or commercialize, this focus on process tends to fade into the background again.

Meta-Reflection: Art Movements and the Five Stages of Grief

You proposed that artistic movements echo the five stages of grief:

Initial shock/denial of the current state,

Anger or rebellion (e.g., against industrialism),

Bargaining (synthesizing tech and craft),

Depression (disillusionment or decay),

And finally, acceptance (integration and innovation).

This metaphor became a way to situate Bauhaus within a larger cycle of artistic evolution.