A Monstrous Instrument of Repetition

The use of doubles, clones and twins in physical environments and horror

I have slept soundly most of my life. No matter what is happening in my life, find me a flat surface and I’ll probably fall asleep in ten minutes. But in some seasons, I fall into the habit of waking up at 3 a.m. with panic in my heart. I go from deep slumber to pupils dilated like Uma Thurman in that one scene from Pulp Fiction where John Travolta sticks a syringe full of adrenaline into her heart. Then I pace around the house to make sure the doors are locked, and later lie in bed cataloging every little sound of the night. It started when I lived in Houston. Actually, that’s not true. It started some time during my childhood, but for the purpose of narrative continuity let’s imagine it began in Houston in 2017—right around the time I moved to the United States.

Often, I was up at 3 a.m. — walking around my undecorated, sparsely furnished apartment to make sure there were no intruders. One of my fears at that time was that someone would accidentally walk into my apartment, which looked exactly like all the other apartments in the complex. They’d probably be drunk or really drowsy when they stumbled into the bedroom to find an intruder sleeping there, and then they’d shoot me, the intruder. Then my murder would go to court but get dismissed as an accident. The prosecutor will then tell my bereaved parents, “I guess that’s just life in the big city.”

This amorphous fear was informed by my own experience of moving to the apartment—my first in the United States—and getting turned around or confused several times in my first month of living there. It did not help that one night, a completely sober man walked into my apartment, saw me, paused, exclaimed “Oh shit,” and then backed out of the apartment, never to be seen or heard from again. I definitely lost even more sleep when I read about the Dallas cop who walked into her apartment, saw an intruder, and shot him on sight—only to realize that she had walked into the “intruder’s” house and not hers.

A sense of droning repetition is built into a place like Houston (and Dallas, apparently). The details of the landscape do not register because you are mostly passing over places at 65mph on the freeway. Remembering numbers—exits, buildings, highways—became much more important than landmarks. The city makes you feel like you’re playing Tetris inside an Excel sheet. There were a lot of identical doubles in my lived environment—something that I was not used to in India. The grocery aisles looked the same; I could not differentiate one strip mall from another. Even at ground level, I could not tell what part of the park trail I was on based on the cemented pavement and the grass. It seemed to me that I was often a chummy hamster on a spinning wheel, never really going anywhere but always moving a lot.

It was also a tough time in my life—I was in a strange place without much money and without a single friend—so it is possible that the doubling effects I observed were a product of my own psyche. I had a tough time separating my own emotions and internal selves, and maybe that got reflected back in my reality as well. Perhaps what I was experiencing was simply a subjective temporal collapse that led me to think that “everything is the same, including the lived environment.”

Freudian to Koolhaasian Doubles

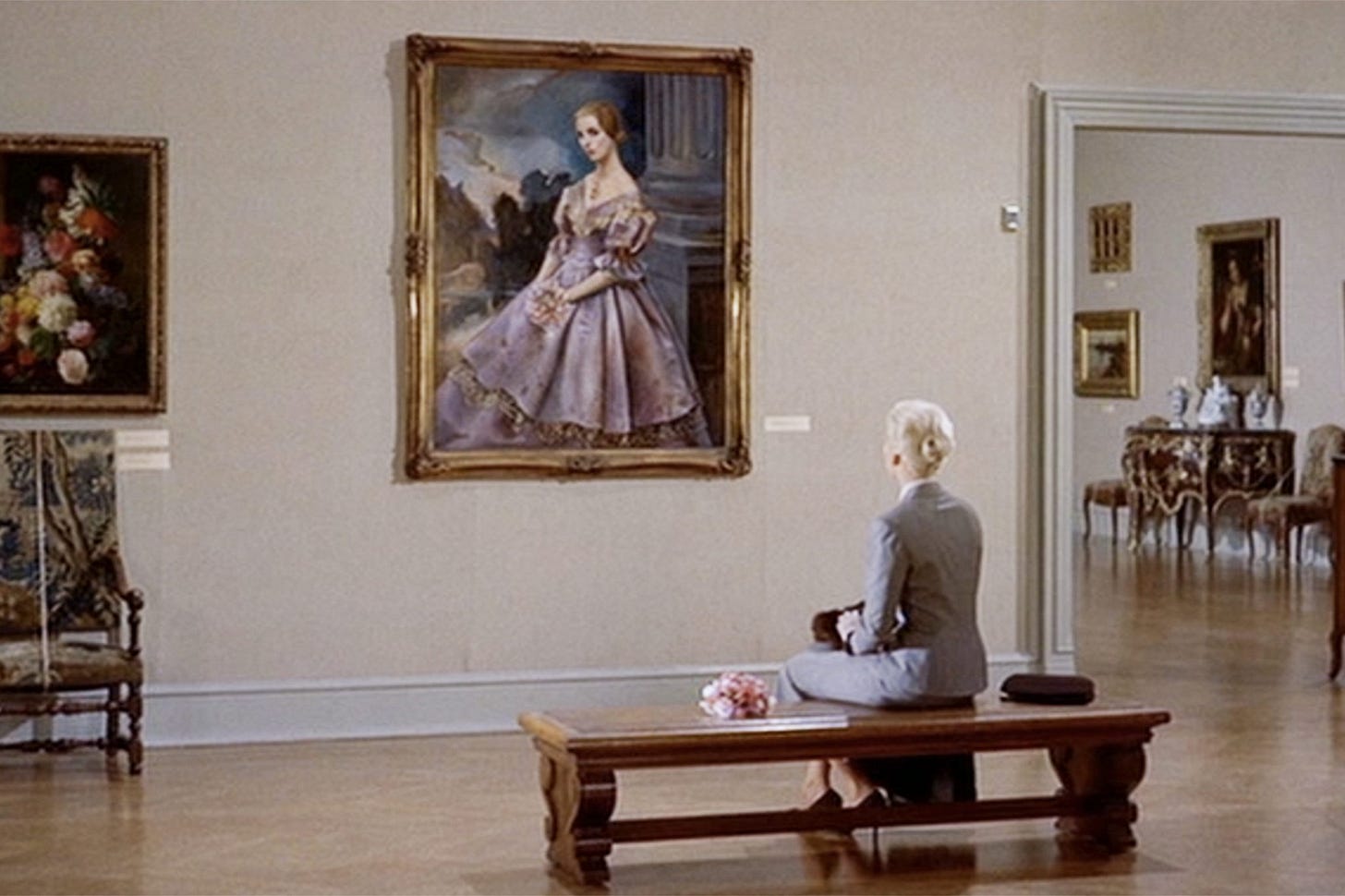

Stories and movies often use the weirdness of identical objects and experiences as a motif for the collapse of time. In Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, former detective John “Scottie” Ferguson (played by Jimmy Stewart) becomes so obsessed with the memory of Madeleine Elster—his erstwhile lover who died by suicide—that when he encounters Judy Barton, a downtown acquaintance, he painstakingly remakes her in Madeleine’s image, dressing her, styling her hair, and even coaching her mannerisms until she seems to rise, ghost-like, from the past. The crucial moment of transformation—when Judy Barton comes into the room looking exactly like Madeleine—dissolves into a shot of Jimmy Stewart inside his car near the church spiral where Madeleine committed suicide, and in that moment both the viewer and the character feel like they are back at the beginning of the loop again—the moment where the protagonist lost the original Madeleine. The same sequence of events is about to begin its doomed spiral.

The Shining is another movie that uses doubles and mirror images — to communicate the collapse of Jack Torrance’s life as a loving father and homicidal caretaker. Both the these movies use doubles as Freudian symbolism for your shadow, guardian spirits…fear of death, but my experience in Houston had mass-manufacturing and mechanical-reproducibility elements as well. It was not just my subjective consciousness that was doubling; it was also external to me, part of a reality that did not go away if I just stopped believing in it.

Mechanical reproducibility is the triumph and terror of our times. When Rem Koolhaas wrote Junkspace in 2001, mechanical reproducibility had all but conquered the physical environment. Architecture went from the status of the last public art to a set of protocols that could be bundled or unbundled to produce glass monoliths and suburbs that multiplied endlessly. Ironically and tragically, the year Junkspace was published also happens to be the year the Twin Towers were destroyed, and footage of the two identical towers collapsing could be interpreted as a cultural artifact of the horror of mechanical reproduction.

Fielder Method

I’ve been watching the new season of The Rehearsal, a show in which the creator, Nathan Fielder, goes into painstaking detail to recreate environments and entire lives of people. Fielder’s work began with sketches in Nathan For You, where he plays a business consultant coming up with elaborate marketing schemes for small businesses. His shows since have gotten stranger and eerier—often with extensive use of doubles and simulated environments that resemble the original.

There are predecessors to what Fielder is doing, such as Jacques Tati’s Playtime and Traffic—both of which use contraptions and visual gags to critique modern corporations and protocols. But both of those have a twee innocence about them, because they were made in a time when people were more hopeful about technology and its influences. Fielder’s reproductions and doubles, on the other hand, are eerie and unsettling. In the new season of The Rehearsal, centered around pilots and airline safety, doubles and clones play a bigger role than in previous productions. The third episode in the season begins with a couple who has cloned three versions of their dead Chihuahua named Achilles. Although the dogs share the same DNA, they behave differently from the original Achilles because they have been brought up differently. So Fielder recreates the exact environment in which Achilles grew up, down to the San Jose air that the dog was used to. There are also several scenes of people being mirrored by doubles—either as a recreation of a particular relationship in a studio apartment or as “packs” (as Fielder calls them)—groups of people mirroring, in real time, the behavior of someone they are assigned to. Through all these identical reproductions, Fielder asks the same questions over and over again: Can a reproduction of something recreate the genius of the original? At least a tiny bit? And can reproducing something teach us anything or inspire us? Or should we treat every reproduction with a life of their own?

Epilogue

For several years after living in that Houston apartment, I’ve thought about writing a short story about a man whose house is invaded by a stranger. The stranger convinces the tenant that the home belongs to him, and the tenant starts to believe him. He begins apologizing and getting anxious about where to go. But the stranger tells the tenant that he can live there with him if he practices the exact same habits and routines as the stranger. The tenant agrees because he’s helpless. Several weeks go by, and one day the tenant returns to the apartment to find a different stranger in the house, who has a different set of demands and routines if the tenant is to remain there. The cycle keeps continuing until the tenant loses any semblance of identity. He becomes a shell inhabited by other people’s dreams.

***

More links:

This piece by

on capgras syndrome as metaphor for the Anthropocene was an inspiration for my post:

Horror in Architecture: First chapter in this book deals with doubles and clones in architecture.

A lot of doubles in pop culture too lately- Severance, Mickey 17, The Substance

Great piece! Pinterest does a trend prediction every year and one of this year’s trends is projected to be ‘Seeing Double’ — twins, doppelgängers, and mirrors everywhere. Super ominous given your framing here!