Everyone Is On Something

Free Energy Principle, AI agents and general economy of surplus

Speaking with people who extensively use AI often feels like speaking with someone who is on drugs. If you are on a Zoom call with them, their eyes are drifting to whatever their agents have been working on in the background. The conversation often takes a hypomanic tone. They either text long paragraphs or one-word replies. It seems like using AI, particularly agents like Claude Code, has much deeper psychic penetration than previous technology paradigms such as the smartphone or the internet. As someone at Summer of Protocols put it, AI will create new types of people.

In order to understand what kinds of people it might create, it is useful to look at existing research on how the brain gets rewired by psychedelics. There are several frameworks for investigating this, but Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle is probably the most fitting — not only because it offers a computational account of belief revision and cognitive rigidity, but because it is built on the same information-theoretic foundations as Shannon entropy. There is a medium-is-the-message quality to using an information theory of mind to analyse the effects of an information technology, and that resonance makes it a compelling lens.

I don’t claim to have a full understanding of Friston’s ideas, but its worth investigating if there’s a there there.

This is High Background Steel, the AI slop division of Summer Lightning. These are experiments in AI writing with the conceptual process sometimes listed at the bottom. You can opt out of this section of the newsletter if its not your vibe.

I. The Architecture of Stuck

The human brain, according to Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle, is fundamentally a prediction machine. It maintains a hierarchical generative model of the world—a layered architecture of beliefs, from low-level sensory expectations to the most abstract, compressed priors at the top of the hierarchy: who you are, what the world is like, what is possible. These high-level beliefs, housed in what neuroscientists call the Default Mode Network, function as an executive summary of reality. They constrain and contextualise everything below them. They are, in the language of information theory, low-entropy attractors—stable states the system returns to because they successfully compress an enormous amount of incoming data into a manageable narrative.

This architecture works well. It allows you to navigate a complex world without being overwhelmed by raw sensation, because most sensory data is predicted in advance and only the deviations—the prediction errors—require processing. The system minimises what Friston calls variational free energy, a quantity closely related to Shannon entropy that serves as an upper bound on how surprised the organism is by its own experience. A well-functioning brain is one that is rarely surprised, because its model of the world is accurate enough to anticipate most of what it encounters.

But the same architecture that enables efficient prediction also creates the conditions for pathological rigidity. In depression, the high-level priors become excessively precise—over-weighted, resistant to revision, self-referentially reinforced. The depressed person’s generative model has settled into a deep attractor basin: I am worthless, nothing will change, effort is futile. These beliefs are not merely thoughts. They are the computational parameters through which all incoming experience is filtered. Positive events are explained away. Contradictory evidence is suppressed by the sheer precision of the prior. The Default Mode Network becomes hyperconnected, running the same loops with increasing confidence, and the system’s free energy landscape develops a single deep valley from which escape becomes progressively more difficult.

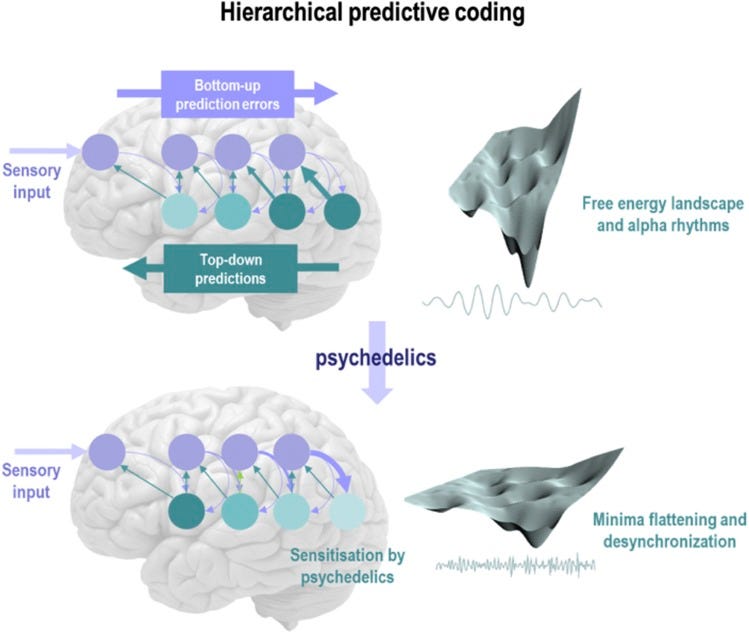

This is what Robin Carhart-Harris and Karl Friston describe in their REBUS model: Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics. The “beliefs” in question are not propositional attitudes but the precision-weighted priors at the top of the cortical hierarchy. The “relaxation” is a reduction in the confidence the brain assigns to its own highest-level predictions. The mechanism is remarkably specific: psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin act primarily on 5-HT2A serotonin receptors, which are expressed with particular density in the high-level cortical areas that instantiate the Default Mode Network.

When these receptors are activated, the computational effect is a flattening of the free energy landscape. The deep attractor basins that held cognition in place become shallower. Prediction errors that were previously suppressed by confident top-down priors now propagate upward through the hierarchy, reaching levels they normally never access. The subjective experience is profound: ego dissolution, perceptual flooding, the sense that familiar categories are dissolving. But the computational reality is more significant than the phenomenology. The system has entered a state of heightened entropy—more neural configurations become accessible, more states become equiprobable, and the generative model becomes temporarily plastic in a way that permits fundamental restructuring.

Friston and Carhart-Harris draw an explicit analogy to simulated annealing in optimisation. A system is “heated” to escape local minima in a cost function, allowing it to explore a broader solution space before “cooling” into a new, potentially more optimal configuration. Psychedelics heat the brain’s belief system. The pathologically rigid priors of depression, addiction, or trauma are temporarily destabilised, and during this window of plasticity—guided by therapeutic context, preparation, and integration—the system can settle into new, more adaptive attractor states. The clinical evidence is striking: single or few guided psychedelic sessions can produce lasting improvements in treatment-resistant depression, end-of-life anxiety, and addiction, with effect sizes that dwarf conventional pharmacotherapy.

The key insight is not merely that psychedelics disrupt rigid beliefs. It is that they do so by acting on the deepest, most abstract level of the brain’s architecture—the level that furnishes beliefs about domain-general narratives regarding the world, qualities of self, and states of being. These are not beliefs about specific facts. They are the beliefs that structure how all other beliefs are held. When these priors are relaxed, the perturbation cascades through the entire hierarchy, from the most abstract sense of selfhood down to the raw geometry of visual perception.

II. The Annealing of Work

Consider now a different kind of rigidity. Over the course of a career, a knowledge worker develops a deeply entrenched generative model of what work looks like. A senior software engineer “knows” that refactoring a legacy codebase takes two sprints. A writer “knows” that research for a long-form piece takes days. A designer “knows” the iterative cycle from brief to final deliverable. These are not merely time estimates. They are high-precision priors about the structure of problems, the sequence of subtasks, what is feasible, and crucially, what is worth attempting. They sit at the top of a professional cognitive hierarchy and filter what you even consider trying.

Like the depressive’s beliefs about selfhood, these professional priors are locally accurate but globally suboptimal. They were calibrated in a world without the tool. They create deep attractor basins—you keep approaching problems the same way because your model says that is the shape of the solution space. You do not explore because your priors tell you exploration will not pay off. The free energy landscape of your professional identity has a single deep valley, and you have been in it long enough that you cannot see its walls.

AI agents—tools like Claude Code, Cursor, and their rapidly evolving descendants—are performing something structurally analogous to what psychedelics do in the REBUS model. They are relaxing the precision of high-level professional priors. When a task you “knew” took a week gets completed in an hour, the prediction error that arrives at the top of your professional hierarchy is massive. And unlike a one-off anomaly that can be explained away, AI agents deliver these prediction errors repeatedly and systematically, across domains, at increasing intensity. The priors cannot hold.

What follows is a phase of genuine epistemic foraging. In Friston’s active inference framework, agents do not merely act to confirm existing beliefs; they also seek out information that reduces uncertainty about the world. When high-level priors are relaxed—whether by psilocybin or by the sudden discovery that your professional model of feasibility is wrong—the system shifts toward epistemic mode. New possibilities become thinkable. You begin to explore regions of the professional landscape that your previous priors had rendered invisible. The free energy in the system increases, because the old model no longer compresses reality efficiently and the new model has not yet consolidated. You are, computationally speaking, in the heated phase of an annealing process.

But here the analogy with psychedelics develops a crucial divergence. Under LSD or psilocybin, the subject lies on a couch with eyeshades, turned inward. The relaxation of priors produces a state of receptive openness—ego dissolution, surrender, the dissolution of agency into experience. The therapeutic power lies precisely in this passivity: the system is freed from its habitual patterns and allowed to reconfigure without the interference of goal-directed action.

AI agents produce a fundamentally different phenomenology, because you are not lying still. You are acting. You are engaged with an intelligence outside yourself, co-creating at speed, watching possibilities materialise in real time. The prior relaxation is happening—your beliefs about what is possible are being dismantled—but simultaneously, the task-positive network is activated at high intensity. You are not merely discovering new states; you are building in them, navigating them, acting on them. The Default Mode Network is being perturbed while the task-positive network runs at full power.

This is, in neurological terms, the signature of hypomania. In normal cognition, the Default Mode Network and the task-positive network operate in anticorrelation: when one is active, the other is suppressed. They take turns. In hypomania, this anticorrelation breaks down and both networks become simultaneously active. The self-model does not dissolve as it does under psychedelics—it expands. Every idea feels profound, every connection feels real, every project feels achievable. The generative model at the top of the hierarchy becomes more encompassing, more confident, while remaining decoupled from the error-checking mechanisms that would normally constrain it.

This is the hypomanic edge that AI agents introduce into knowledge work. The professional who has discovered that their old model of feasibility was wrong, and who is actively building with tools that keep confirming the expanded model, experiences something phenomenologically close to a hypomanic episode: accelerated ideation, compressed timelines, a feeling of limitless possibility, reduced need for reflection, a sense that old constraints were arbitrary and that the real shape of the possible is only now becoming visible. The crucial question—the one that separates productive transformation from hypomanic inflation—is whether this expanded model is being tested against reality or insulated from it.

Under psychedelics, the question resolves itself. The drug wears off. Precision returns. Integration happens in the sober aftermath, with a therapist, in the cold light of day. The annealing has a cooling phase built in. AI agents offer no such natural limit. The tool is always available. The prediction errors keep arriving. The temperature never fully drops. The system remains in the heated, exploratory phase indefinitely—permanently foraging, permanently in surplus, permanently needing to burn.

And here, inevitably, we arrive at Georges Bataille. The epistemic foraging generates surplus. Not just economic surplus—cognitive surplus, creative surplus, productive capacity that exceeds what existing structures of work or meaning can absorb. In Bataille’s general economy, surplus that cannot be absorbed by growth must be expended. The only question is how: through glory or catastrophe, through the festival or the war. The knowledge worker whose AI-augmented capacity now vastly exceeds the demands placed upon them is carrying an accursed share of cognitive energy with no established channel for its expenditure.

III. The Entropy Sink: Why the iPhone Was Different

To understand the specificity of this moment, it is essential to compare AI agents with the last technology that restructured daily life at a population level. The iPhone is the obvious case, and the comparison is clarifying precisely because the differences are so stark.

The iPhone did not destabilise high-level priors about identity, capability, or human value. It did not generate a surplus of cognitive energy. If anything, it did the opposite. The iPhone was an entropy sink—a device that absorbed free cognitive energy rather than generating it. Every idle moment that might have previously been occupied by Default Mode Network–mediated mind-wandering, self-reflection, or creative incubation was captured by the scroll. In Fristonian terms, the iPhone provided a constant stream of low-level prediction errors—notifications, feeds, novel micro-content—that kept the system busy at the bottom of the hierarchy without ever disturbing the top. Your self-model stayed intact. You simply had less unstructured time in which to examine it.

The iPhone changed behaviour without threatening identity—at least not directly. Nobody had an existential crisis because Google Maps existed. The technology slotted neatly into existing self-narratives—I am a person who now has a better tool for communication, navigation, entertainment—and the generative model at the top of the hierarchy barely required updating. In Fristonian terms, the iPhone was a task-positive network phenomenon. It activated doing, scrolling, swiping, consuming—but it left the Default Mode Network’s self-model largely untouched. The priors about who you are, what you are capable of, what constitutes valuable human activity: none of these were seriously challenged. The iPhone reinforced existing priors by making you marginally more efficient at things you already did. The cultural affect reflects this: distraction, shortened attention, mild anxiety about screen time—all relatively shallow perturbations operating at the periphery of the cognitive hierarchy. Compare this to the AI moment, which is producing existential vertigo—dread, euphoria, grandiosity, despair, often in the same person in the same week. That emotional signature maps onto DMN destabilisation rather than behavioural modification. The iPhone activated the task-positive network. AI is reaching into the default mode.

But there is a subtlety here that matters. The iPhone may not have penetrated the DMN directly, but it did so indirectly through the oldest backdoor into identity: habit. What you do every day is, eventually, what you are. A decade of reaching for the phone in every idle moment, of replacing reverie with the scroll, of substituting parasocial consumption for unstructured self-encounter—this did not leave the self-model untouched. It just changed it slowly, through the accumulation of behavioural priors rather than through a dramatic confrontation with the generative model. The loneliness epidemic, the adolescent mental health crisis, the erosion of sustained attention—these may represent the long-latency effects of a technology that reshaped the DMN not by challenging it but by starving it of the unstructured input it needs to maintain a coherent self-narrative. The iPhone did not anneal identity. It atrophied it. And this means the current population is one whose Default Mode Network has already been subtly degraded by a decade of attentional capture, now encountering a technology that actively destabilises high-level priors. The containers for integration were weakened before the real perturbation arrived.

The Bataillean analysis sharpens this. The iPhone did not produce an accursed share because it did not produce surplus. It consumed existing surplus. It was a spectacularly efficient channel for burning the small amounts of free cognitive energy that daily life naturally produces. One could argue that the iPhone era actually suppressed the kinds of expenditure Bataille valued most. It replaced potentially sovereign moments—boredom, reverie, unstructured encounter with one’s own interiority—with servile micro-consumption. Every scroll was expenditure in service of the attention economy’s accumulation. The energy was burned, but in the smallest denominations, at the lowest temperature, in service of someone else’s growth.

IV. The Narrowing: GLP-1 Agonists and the Pharmacology of Desire

If AI agents represent an annealing of possibility—a relaxation of priors that broadens the space of what is thinkable and doable—then GLP-1 receptor agonists represent something like the opposite force. They are not expanding the horizon of desire. They are contracting it.

The clinical facts are by now well established. Drugs originally developed for type 2 diabetes—semaglutide, tirzepatide, and their successors—have proven extraordinarily effective for weight loss, and increasingly, for curbing a wide range of compulsive behaviours. Patients report reduced interest not only in food but in alcohol, nicotine, gambling, compulsive shopping, and other reward-driven activities. The mechanism appears to involve modulation of dopaminergic signalling in the mesolimbic pathway, dampening the motivational salience of stimuli that previously commanded attention and action. In Fristonian terms, GLP-1 agonists are increasing the precision of priors related to homeostatic and appetitive regulation, narrowing the range of states the organism is motivated to pursue.

This is not the relaxation of beliefs. It is their tightening. Where psychedelics flatten the top of the hierarchy and AI agents destabilise professional priors, GLP-1 agonists compress the motivational landscape, making fewer states appear attractive, reducing the number of attractor basins the system is drawn toward. The phenomenological reports are consistent: people describe not craving things they used to crave, not thinking about food or alcohol or consumption in the way they once did. The desire itself is attenuated. The prediction errors that once drove seeking behaviour—the felt gap between the current state and the imagined rewarding state—are dampened at source.

In the context of our broader argument, GLP-1 agonists are performing a kind of anti-annealing. Rather than heating the system to enable exploration of new states, they are cooling it further, reducing the temperature below baseline, collapsing the landscape into fewer and shallower valleys. The system becomes less exploratory, less driven, less hungry—in every sense of the word.

Here is where the connection to cultural phenomenon like looksmaxxing and the broader culture of self-optimisation becomes visible. If we accept that an ambient surplus of cognitive and productive energy is creating a Bataillean expenditure crisis—too much free energy with too few sovereign channels—then two opposite responses emerge. The first is to find channels for the surplus: to burn it, redirect it, spend it in ways that are either glorious or desperate. Looksmaxxing, biohacking, protocol culture, the compulsive optimisation of the self—these are all channels for expending surplus through precision-seeking at controllable scales. You cannot control whether your career will exist in five years, but you can control your body fat percentage. The energy has to go somewhere.

The second response is to eliminate the surplus itself. This is what GLP-1 agonists do. Rather than finding adequate channels for excess desire, you pharmacologically reduce the quantity of desire available to be channelled. Rather than learning to burn gloriously, you eliminate the fuel. The problem of surplus is solved by eliminating the experience of surplus.

Bataille would recognise this immediately as the ultimate servile response to the accursed share. The general economy produces excess. The restricted economy cannot absorb it. And rather than accepting the necessity of sovereign expenditure—purposeless, unrecoverable, glorious waste—the system reaches for an intervention that reduces the quantity of energy available. The desire that cannot find an adequate object is not redirected or sublimated or spent in a festival of destruction. It is chemically quieted. The fire is not given somewhere to burn. The fire is put out.

The parallel between looksmaxxing and GLP-1 use is instructive because both are responses to the same underlying condition—a destabilised meaning landscape in which traditional channels for desire and expenditure have become unreliable—but they represent opposite strategies. Looksmaxxing attempts to solve the problem through more expenditure, more discipline, more protocol, more control. GLP-1s attempt to solve it through less desire, less craving, less motivation, less fire. One is servile expenditure disguised as sovereignty. The other is the abolition of the need for expenditure altogether.

Neither is sovereign in Bataille’s sense. The looksmaxxer keeps a ledger; every sacrifice is an investment in future returns. The GLP-1 user simply exits the economy of desire. Both refuse the fundamental Bataillean challenge, which is to spend without return, to burn without purpose, to accept that the surplus is not a problem to be solved but a condition to be inhabited.

V. Coda: The Temperature of the Age

We are living through a moment in which the temperature of the cognitive landscape is being manipulated from multiple directions simultaneously. AI agents are heating the system—relaxing professional priors, generating surplus, forcing epistemic foraging at a pace that outstrips the capacity for integration. GLP-1 agonists are cooling it—narrowing desire, compressing the motivational landscape, reducing the energy available for expenditure. The iPhone, in retrospect, was merely a thermostat that kept things comfortable while quietly preventing the kind of unstructured experience from which genuine transformation might have emerged.

The Fristonian framework gives us the computational vocabulary: prior relaxation, precision weighting, free energy minimisation, the annealing of belief systems. Bataille gives us the economic vocabulary: the accursed share, sovereign versus servile expenditure, the necessity of waste. Neither framework alone is sufficient. Together, they suggest that the defining challenge of the present is not the technical question of what AI can do, or the medical question of what GLP-1s can treat, but the existential question of what to do with a species whose cognitive surplus is growing faster than its structures of meaning can metabolise.

The people who thrive in this landscape will be those whose generative models are flexible enough to undergo genuine revision—who can tolerate the heated phase of the anneal without either collapsing into hypomanic inflation or reaching for pharmacological cooling. They will be the ones who develop what Bataille might call rituals of expenditure adequate to the surplus: ways of burning that are neither anxiously productive nor chemically suppressed, but genuinely, purposelessly alive.

Whether such rituals can be developed at scale, or whether the surplus will find its own channels—glorious or catastrophic—remains the open question. Bataille would remind us that the energy does not wait for our answer. It is already being spent.