Manufactured Present

Casino Time, Craft Time and expression of time in risks x consequences

When I was in Berlin this October, I took Ubers twice. Both times it seemed like the driver was playing the role of a man who had to get to the other side of the city before a bomb went off. They cussed under their breath, merged using turning lanes, shouted at drivers while driving at 50 kph through crowded streets. In between all this, they turned to me with the softest smile and asked me if everything was good. I white-knuckled both hands inside my jacket pockets.

Later, I recounted this to a friend from India who had moved to Berlin, who—rather than sympathizing with me—proceeded to tell me all his troubles in getting a car license in Germany. Apparently, it costs at least 2,000 euros to get a driver’s license. Up to 4,000 euros if you’re taking the test multiple times, which about 50% have to. The question bank for the written part of the test is 1,200 questions, compared to the US, where you have to memorize a 10-page pamphlet of basic questions. Driving lessons are compulsory. The practical test is also strict. All of this means that Germany has one of the safest roads in the world, even though every taxi driver drives like Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible 2.

The US, on the other hand, has eight times the pedestrian death rate per distance walked compared to Germany (≈11.2 deaths per 110 million km walked vs. ≈1.4 in Germany), based on data from 2016–2018.

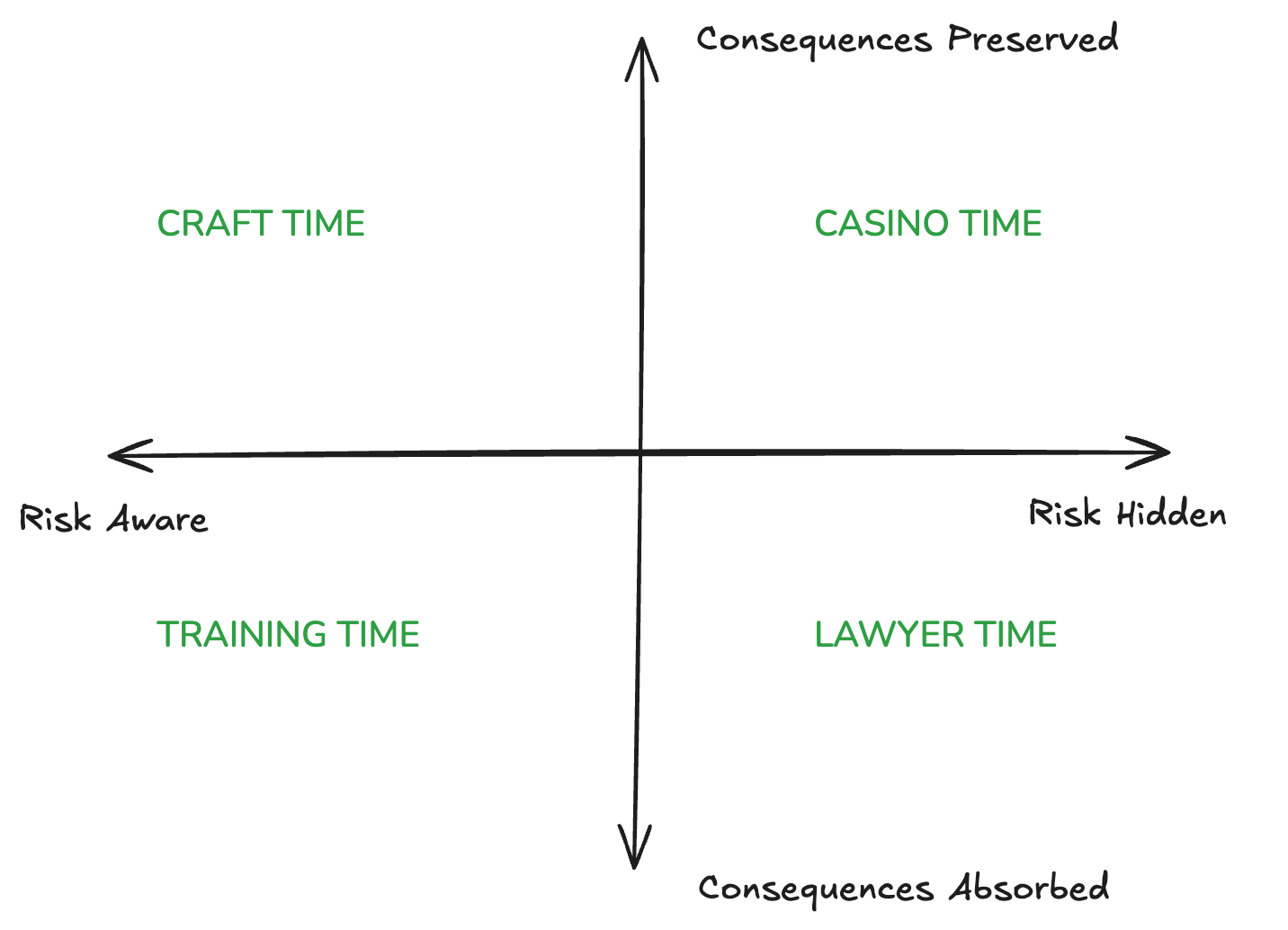

Risk X Consequence 2X2

German traffic culture is focused on managing risk by emphasizing strict pedagogy and a higher barrier to entry. They are able to do this because you can still get around German cities using trains and a well-developed biking system. American traffic culture, by contrast, has a much lower barrier to entry, with the focus on enforcement of traffic rules by police. In the latter case, the consequences of bad driving are absorbed by law enforcement, while in the former case, the consequences of bad driving are handled at the pedagogy level. This calls for a 2×2 of how different cultures handle risk (legible vs. illegible) and consequence (absorbed or preserved).

Once you frame safety this way, it stops being a question of how much risk a system allows and starts becoming a question of how risk and consequence are experienced in time. Some systems make risk legible: you can see it, feel it, anticipate it. Others hide it behind smooth interfaces, barriers, automation, or assurances. Likewise, some systems allow consequences to be felt—to register in the body, the memory, the future—while others work hard to absorb them, buffering mistakes before they can propagate. Put differently, safety cultures differ not only in how much danger they tolerate, but in whether they allow people to feel time moving forward as consequence, or whether they flatten experience into a continuous, consequence-free present. The four combinations of these choices produce four very different kinds of worlds.

Craft Time & Training Time

Craft Time is where honor- and craft-based cultures operate. Cultures like mountaineering and bouldering seem to have a strong ethos around making participants aware of risks, partly because the participants are exposed to consequences more directly. You could also apply this to work that involves staying in the present moment and working with real raw materials, such as being a chef or doing woodworking. The first quadrant (risk made aware, consequences preserved) is also where the German driving system partially operates.

But Craft Time is not self-sustaining. Without institutions that train judgment, without shared norms, without some background layer that absorbs mistakes while people are learning, legible risk collapses into pure exposure. Consequences are still felt, but no longer meaningfully. Time becomes predatory rather than instructive. This is the Hobbesian edge of the quadrant: everyone for themselves, speed as dominance, survival as the only lesson. Honor time curdles into brute time.

The German driving system works because of a strong quadrant three, where drivers are tested rigorously while the consequences of mistakes are absorbed by the training regime. The cost, repetition, and difficulty are not incidental; they are how anticipation is installed. Long written exams force saturation with edge cases. Strict practical tests surface hesitation and mistiming rather than basic incompetence. Mistakes are expected, but they occur in an environment designed to metabolize them safely.

Training Time shows up wherever people are preparing for irreversible action without being exposed to it too early: flight simulators, surgical residencies, apprenticeships in skilled trades, martial arts dojos, probationary licensing systems. In each case, risk is legible, but failure is bounded.

Without this layer, the Craft Time quadrant collapses into brute exposure. Risk is still visible and consequences still felt, but experience no longer compounds into skill. Training does not eliminate danger; it ensures that when danger arrives, it arrives to someone who already knows how to live inside it.

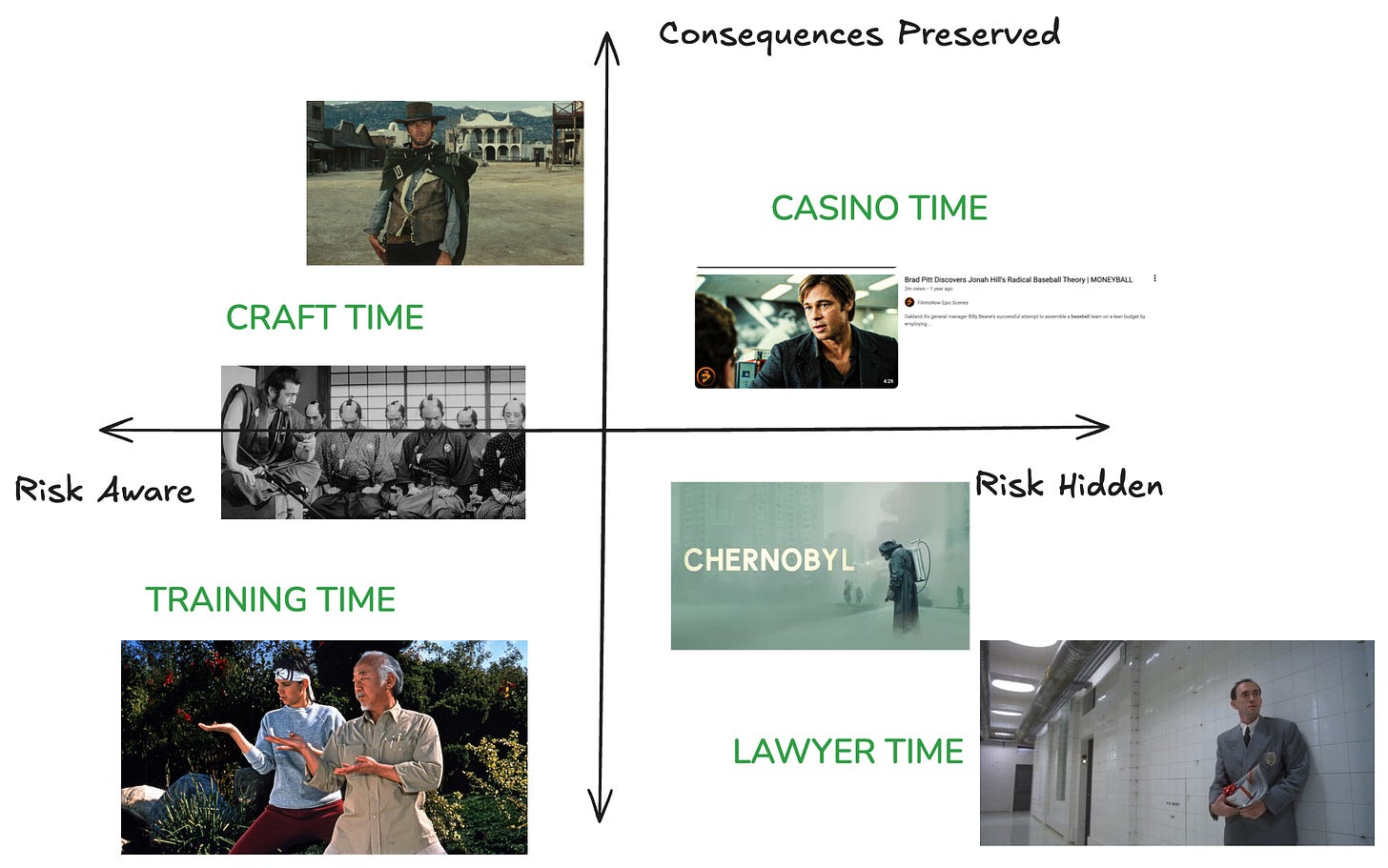

Craft Time and Training Time stories

Westerns, particularly the John Ford variant, seem like a good example of pure Craft Time. The characters in western films have varying levels of skill with a gun, with the hero usually being the most skilled. Everyone is aware of the risks in a frontier, lawless western town and relies on individual skill to survive. Kurosawa’s western-inspired adaptations such as Sanjuro perhaps best embody westerns as Craft Time backed by Training Time. In Sanjuro, the lead character is a highly skilled wandering samurai, working together with a band of amateur samurai who are yet to understand the risks at stake. By the end of the movie, the wise but wayward samurai has taught the young amateurs the risks at hand, leaving them better prepared to handle Craft Time.

Chivalric romance tells a different kind of Craft Time story, even though the risks are just as real. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain accepts a blow from the Green Knight knowing that the knight will return a year later to deliver the same blow. The narrative unfolds inside that deferred consequence. What makes the story possible is not Gawain’s bravery, but the existence of a shared code that gives meaning to the waiting. The knight’s code—honor, oath-keeping, restraint—functions as a training layer beneath the Craft Time action. It tells Gawain how to live inside the time he has created for himself.

Casino Time & Lawyer Time

Casino Time is defined less by danger than by temporal obscurity. Risk is not eliminated; it is concealed. The system works by interrupting the user’s ability to feel time unfolding, even as consequences remain fully intact. Outcomes still arrive, often suddenly and irreversibly, but the path toward them is deliberately blurred. Time is compressed, disoriented, and stripped of markers that would allow anticipation or reflection.

Las Vegas is the canonical example. Clocks disappear. Windows vanish. Credit is extended and revoked with little friction. The design does not remove risk; it accelerates exposure to it by severing the feedback loops that normally regulate behavior. The feeling of luck is the feeling of time collapsing into the present. Each bet carries real consequence, but without the temporal cues that would allow judgment to accumulate. Winning and losing both feel provisional, which is why the next hand always seems to matter more than the last.

What makes Las Vegas effective is not deception in the narrow sense, but temporal manipulation. By hiding duration, fatigue, and accumulation, the environment converts time into a series of isolated events. Consequence is preserved, but memory is weakened. Losses do not teach; they reset. Wins do not stabilize; they provoke escalation. Time no longer instructs—it churns.

Lawyer Time emerges when systems attempt to absorb more consequence than they can meaningfully carry. Laws, regulations, constitutions, compliance regimes, and safety frameworks expand not just to manage risk, but to pre-empt it entirely. People are treated as agents who must be protected from themselves—from misjudgment, from ambiguity, from future claims. Risk is not clearly presented; it becomes diffuse, procedural, and abstract. Consequences are presumed to have already been handled somewhere upstream.

In its early forms, this kind of consequence absorption represents real progress. Seat belts, building codes, clinical standards, and liability law all reduce baseline harm. They remove obvious, structural dangers that no amount of individual judgment should have to compensate for. The problem appears when absorption continues past the point where it can still educate. As more risk is displaced into systems, the signals that once guided judgment grow faint. Responsibility is redistributed, then diluted. Time flattens into compliance cycles rather than lived anticipation.

You can see this logic clearly in waiver-saturated environments. Gyms, events, platforms, and medical offices present pages of legal language that formally acknowledge danger while doing almost nothing to make it legible. Risk is recognized in law but obscured in experience. People sign, then stop thinking. The system has absorbed liability, but it has also absorbed attention.

The same pattern appears in overdetermined regulatory systems. Building codes optimized for rare edge cases become universal defaults. Medical protocols expand until they protect institutions more reliably than patients. Enterprise risk management turns danger into dashboards, attestations, and audits. In each case, the system promises safety by replacing judgment with compliance. Risk does not disappear, but it becomes hard to locate.

Casino Time & Lawyer Time Stories

Kafka’s stories are an obvious example of Lawyer Time at work. In The Trial, the protagonist is prosecuted for a crime, but we are never shown what the crime is. Risk is omnipresent, but we are never shown what the risks are.

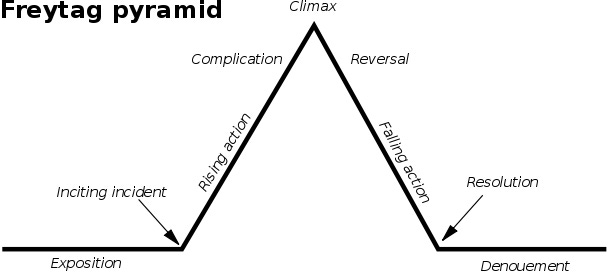

Casino Time stories are probably the ones people are most familiar with. Uncut Gems, Rounders, Moneyball—all operate inside a world where risk is partially hidden, consequences are very real, and time is experienced as a series of accelerating turns rather than a continuous arc of learning. Hollywood returns to this structure again and again because it maps cleanly onto the Freytag triangle. Rising action thrives on concealed exposure. Tension builds because characters are unaware—or only dimly aware—of how much risk has already accumulated.

In these stories, the inflection points of the triangle mark moments when hidden risk becomes visible. A debt is suddenly called in. A streak breaks. A trade backfires. The climax is rarely a surprise in moral terms—it is a temporal one. Time, which had been suspended or compressed, snaps back into view all at once. At the end of Uncut Gems, the live-player gambler played by Adam Sandler places the ultimate parlay bet and meets the ultimate consequence that risk can bring: death.

Feeling Time

In The Scent of Time, Byung-Chul Han introduces three different experiences of time: historic time, mythic time, and point time. Historic and mythic time are forms of time that carry scent. They unfold through duration, tension, and consequence, binding moments together into narratives that can be remembered and anticipated. Historic time is cumulative and irreversible: actions persist, institutions form, and the past presses visibly on the present. Mythic time is exemplary rather than linear, returning to charged moments that structure meaning across generations. In both, time has depth and weight because it unfolds. Point time, by contrast, is time stripped of duration and narrative. On this he writes:

“Time begins to emit a scent when it gains duration; when it is given a narrative or deep tension; when it gains depth and breadth, even space. Time loses its scent when it is divested of all deep structure or sense, when it is atomized or when it flattens out, thins out or shortens. If it detaches entirely from…”

Perhaps the manifest effects of the meaning crisis—namely, everything becoming either a bet or an attempt to approach everything with a craftsman’s attitude—are two sides of the same coin. They are attempts to feel the thickness and duration of time. But both pure Craft Time and pure Casino Time have their failure modes.

In both Craft Time and Casino Time, there is a greater readiness to build a superstructure for reality (the present) along a vertical axis of upper and lower than to move forward along the horizontal axis of time. When these vertical structuring principles become other-worldly, idealistic, eternal, or outside time, their extratemporal quality is experienced as simultaneous with the present moment—as something fully contemporaneous. What already exists is thus perceived as more real, more persuasive, than a future that does not yet exist and may never exist at all.

From the standpoint of present reality, Craft Time prefers the past—more weighty, more fleshed out, more authoritative—while Casino Time prefers a purified present, stripped of both past obligation and future consequence. In different ways, both forms replace forward movement with vertical immediacy. They privilege structures that stand outside horizontal, linear time altogether, yet function as if they were fully real, fully present, and fully sufficient now.

What disappears in both cases is historic time—the felt sense that time moves forward, binds action irreversibly, and demands something new. We have previously felt historic time through conceptual cameras (economics, information theory, modern AI) that imposed a dispassionate awareness of accumulation and consequence. Something like that discipline must return.

***

This is part of a series on Archival Time, where I investigate the new cultural temporality introduced by LLMs. You can find the rest of the posts in this series here

Additional LLM Notes

Failure Mode of Craft Time & Casino Time

Craft Time fails when risk remains legible and consequences remain real, but the conditions that allow experience to compound into judgment erode. The most common failure is brutalization. Without training institutions, shared norms, or informal codes, consequence stops teaching and starts merely sorting. Time becomes predatory rather than formative. Skill still matters, but only narrowly; survival depends less on judgment than on speed, force, or luck. The craft collapses into technique without meaning. What once disciplined attention hardens into vigilance, suspicion, and exhaustion.

Another failure mode is heroic overconcentration. When systems rely too heavily on individual mastery, risk pools around a few experts. Craft becomes rare, fragile, and difficult to transmit. When those individuals fail, retire, or disappear, the system reverts abruptly to chaos. Time teaches, but only a few are allowed to learn.

In both cases, Craft Time stops producing adults and starts producing traumatized veterans: people shaped by exposure, not educated by it.

Casino Time fails by overheating. Risk is hidden just long enough to accumulate, and consequence arrives too quickly to be metabolized. Time is suspended, then returned all at once as shock. Experience does not accumulate into judgment. Losses do not instruct; they provoke escalation or exit. Wins do not stabilize; they intensify exposure.

A second failure mode is addictive looping. When the suspension of time becomes continuous rather than episodic, the system ceases to produce narrative altogether. There is no arc, only repetition. The climax never arrives because the reveal has been normalized. Consequence is still present, but it is abstracted into balances, margins, and churn. Time becomes sticky rather than sharp.

Finally, Casino Time fails socially by externalizing damage. Because exposure is fragmented and obscured, consequences surface elsewhere—debt, breakdown, institutional cleanup. The system appears exciting or neutral at the point of use while offloading its temporal costs onto future selves or other people.

Historic Time

Historic time is felt when human action becomes binding—when what is done cannot simply dissolve back into the present. Byung-Chul Han approaches this phenomenologically. Time gains scent when events interlink, when duration is allowed to thicken, and when moments retain traces of what came before and what is still to come. Historic and mythic time are not fast or slow so much as shaped. They have tension, direction, and depth. Time loses its scent when it is atomized into interchangeable instants—when nothing lingers long enough to obligate memory or anticipation. What disappears is not activity but narrative weight.

Hannah Arendt approaches the same phenomenon from the side of action. For her, historic time emerges when people act in ways that insert something durable into the world. Action is risky precisely because it is irreversible and unpredictable, but it is also what makes history possible. Speech, promises, founding acts, laws, institutions—these are attempts to stabilize the consequences of action long enough for them to matter beyond the moment. Without such durability, action collapses into mere behavior. With it, action becomes something others must reckon with over time.

Taken together, Han and Arendt suggest that historic time is felt at the intersection of duration and responsibility. Han shows that time must linger in order to be experienced as meaningful; Arendt shows that it must bind others in order to be experienced as real. Historic time is not just remembered time, but answerable time. You feel it when the present is constrained by what has already been done, and when what you do now will constrain others later. This is why historic time is inseparable from institutions, promises, and shared worlds. They are not merely records of the past, but devices that force time to retain its scent—to endure long enough for action to have consequences that cannot be privately escaped.

The vertical vs horizontal time distinction is really sharp. What clicked for me is how both craft culture and casino culture end up resisting linear progress, just from opposite directions. I remember working with a small manufacturing shop that obsessed over traditional metalworking techniques but couldn't adopt any new proceses because everything had to be done "the right way." It was pure craft time, but it made them brittle when suppliers changed or clients wanted different specs. The past became more persuasive than adapting to whats actually happening, and eventually they just couldn't compete. The frame about historic time needing institutions that actually bind people across duration makes sense of why that happened.

This is sharp to reframe safety, risk, and culture as temporal design problems rather than moral or technical ones. The Craft/Casino/Lawyer Time split makes clear how many modern systems feel frantic or hollow not because risk vanished, but because time itself has been flattened or manipulated.