It is oddly satisfying to walk through a narrow passageway and enter a brightly lit room with high ceilings. The first time I remember experiencing this was at Uncle Frank's office in the suburb of Chicago. There, a narrow passageway opens into a domed library where Uncle Frank met with clients in the 1900s. The second time was at Luis Barragán's house on a hill in Mexico City. Twentieth century architects loved the little dopamine hit that narrow darkness opening into vast light induced. You could imagine them doing this several times in the afternoon when bored. The image of this particular Luis Barragán room has been regurgitated so many times on mood boards that it took me a minute to be in the actual room and not think of the several thousand times I've seen it in my mind's eye. On the left, when you enter from the passageway, is a staircase which looks like it's floating in midair because of the contrast between the brown tiles and the concrete painted in white. At the top of the staircase, on the wall, is a bright gold rectangle which reflects the sunlight coming in through the giant window to the left. My legs trembled when I walked up the staircase . It seemed to me that I was about to leave this earthly plane forever.

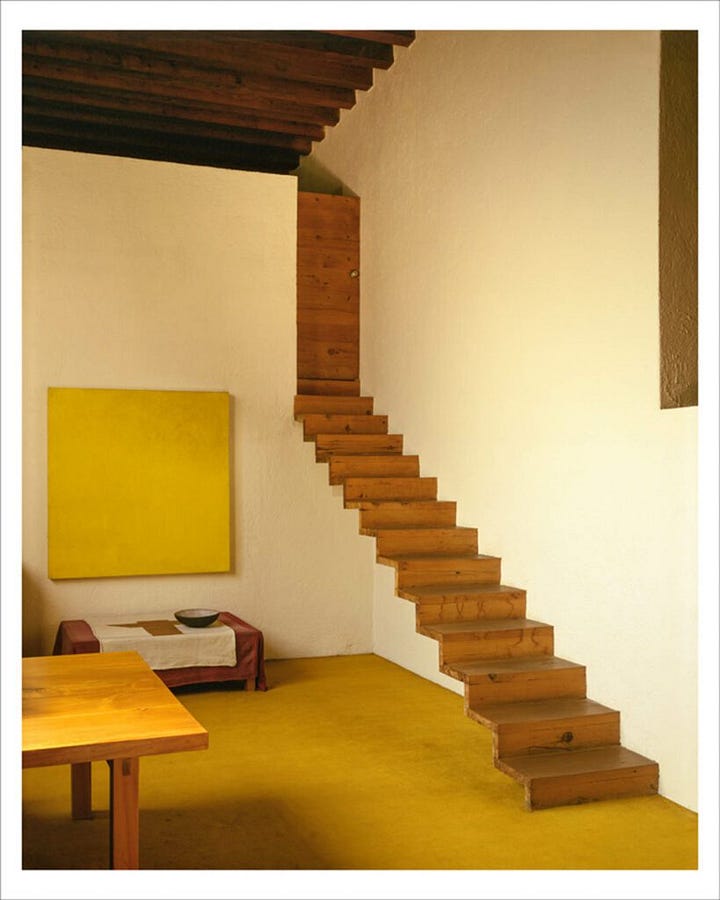

Inside the house, in the cozy readings room, is the same layout as the stairway to heaven but darker. Here the stairs are on the right side of the room instead of the left, and they are actually floating this time, instead of just giving the appearance of floating. At the bottom left is a yellow rectangle, which in contrast to the bright gold rectangle looks like a sun setting in the horizon. At the top of the stair is a door. There is very little light in that corner of the room. The guide with us says "Luis Barragán loved playing with opposites," which seems to be a visual and emotional motif that seems to run through the entire city.

There are the giant pyramids of the Aztecs, which are supposed to tell you a serious version of history about serious rulers like Moctezuma, who conducted so many human sacrifices that it was a full-time job for priests of the time. Then there are the miniatures made of clay or stone. They have a religiosity about them but are also... not serious. Miniature figures of dogs that Aztecs liked to be buried with, miniature gods who look like caricatures from a PG Wodehouse book, obscene miniatures engaged in ungodly sexual acts, miniature mermaids etc. The miniature, small history seems more fun than the blood-soaked giant history.

When the Aztec city of Teotihuacan was first excavated in the 1900s you could just walk right through it and comb for relics to take home. Diego Rivera did this and you can find the little miniatures he collected at the Anahuacalli museum (yet another serious pyramid structure). He collected so many of them which must have occupied so much time that it's hard not to imagine that it took some toll on his marriage. He did get divorced twice before meeting Frida Kahlo, by which time he had collected enough figurines to fill a three-story museum.

The Mayan and Aztec miniatures have a direct lineage to the ones you find at the gift shops — the little skeletons playing the piano, the guy in the sombrero hat, the luchador action figures. You could get them anywhere, even north of the Mexico border but they have an actual life closer to the source. They have the spirit of the small history within them. They are more alive. It's the same with the corn tortilla that you get in Mexico City vs somewhere in Texas — one is alive and the other is a simulation that has been abstracted away from what was once corn.

The tension of opposites is evident in the everyday city as well. There is a general austereness in the interaction between the opposite sexes. Catholicism is still alive here after all. But after the sun sets, the atmosphere is suddenly steamy and there are people making out on every street corner. It seems as if someone flipped a switch and I'm in the opposite of the city I was in during the day. The music on the streets is loud but the bars are usually quiet. The loudest group in the room is usually a bunch of Americans.

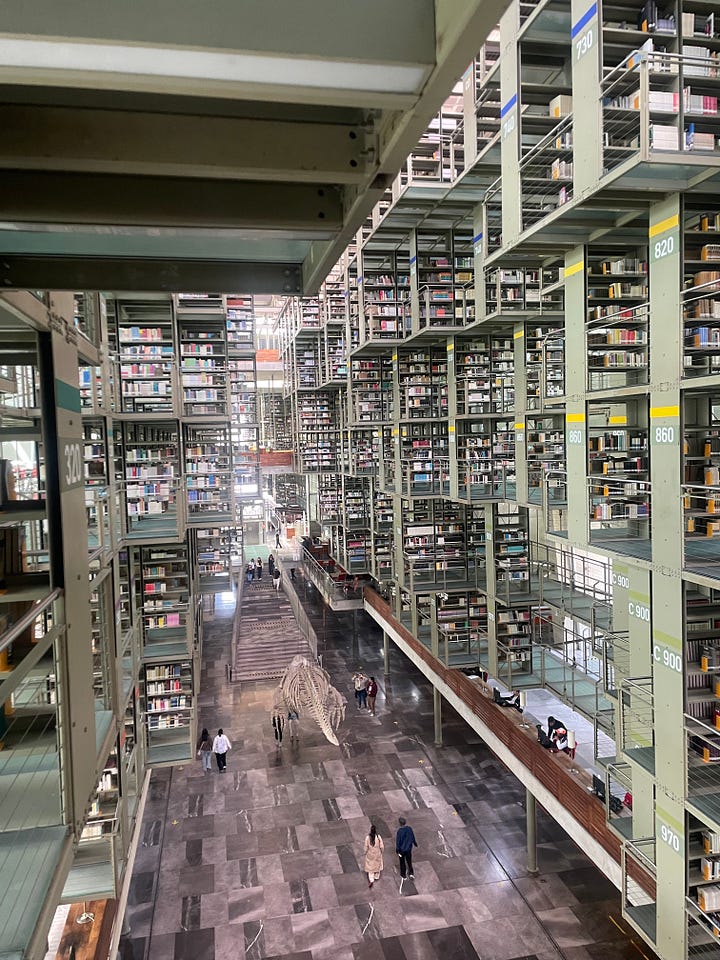

Contemporary Mexico City acknowledges this tension between opposites. The Bibliotheca Vasconcelos, a library that the architect described as Infrastructural Botanical Machine for Learning, is a monumental structure with floating bookshelves and a giant dinosaur skeleton in the lobby. But the library is welcome to everyone. I see everyday folks outnumber tourists. Outside in the garden that surrounds the library, I see people having lunch, walking around, a young woman braiding the hair of her male friend. A big monument where small history unfolds. The garden, the steel and layman use of the structure reminded me of the High Line in New York city — a monumental structure mostly meant for tourists which culminates at The Vessel, a building that is now closed to the public because people were throwing themselves off it.

***

I don’t know the origin of this tension of opposites in Mexico City, but there are a few hints in the history of the city.

After the Spanish conquest of the city, the kids of Nahuatls were educated by Franciscan friars. Sometimes they were taken away from their parents to live in parishes and complete their religious education. In the 1580s, Chimalpahin was likely one of them. He was baptized as Don Domingo. By the age of 11, he had impressed whoever was educating him so much that they decided to send him to Mexico City to continue his education. According to the records he kept, he was a frequent visitor to the indigenous chapel of San Josef de los Naturales, and he liked to go to the zoo at the indigenous community center. Later on, as a young man he would witness the floods of 1606, a tragedy that consumed many lives and caused epidemics to spread through the city. Faced with this, the Spanish decided to drain the central basin of the city, a job that would be done by the indigenous people, in the course of which several thousand more lives would be lost.

As the tragedy unfolded, Chimalpahin came across two books printed in the city in 1606. In Mexico City, friars had been printing books for their own purposes since 1539. Before the printing press arrived, scripture lived in Latin, sealed away from anyone who was not a priest or a noble. When people on Substack write about compression culture and having time to think prior to the invention of printing, I imagine they are talking about scriptures suffocating inside the robes of priests. Then suddenly, post-printing, scripture was available in vernacular languages all over the world, changing the relationship people had with it from divine authority to something personal. The church tried to rein this in during the Counter-Reformation. Printing in native tongues was discouraged because it might “mislead the souls of the ignorant”. But Mexico City was far from Europe and such warnings were ignored. One of the books Chimalpahin found was by a Spaniard named Enrico Martinez who used his knowledge of European encyclopedias and natural history books to write about his new environment — Report on the History and Natural History of New Spain. The other book was by a friar named Juan Bautista Viseo, called Sermons in the Mexican Language, which credited the Nahuatls who had helped edit the book, many of whom were likely known to Chimalpahin.

These works and his education influenced Chimalpahin to begin his own project of writing his people's history, which eventually became one of the primary sources of Aztec history written by a native, one whose family members had lived through the conquest. A foreign language and a foreign technology became the means by which a man preserved the small history of his people — something even the giant pyramids could not accomplish.

Archivists are underrated.

The contrasting frame is apt for CDMX. There’s something peculiar with having to import drinking water into a place that used to be a giant lake. Beautify city.

Did you get a chance to go to the chinampas at xochimilco? Another study in contrasts. The best land to grow food over there is on the water.