Prophetic Soft Technologies

Prediction markets as media that blunts the loss of narrative.

This post is part of a series on Archival Time, where I investigate the new temporality created by LLMs and how it changes our relationship with media.

Prediction is everywhere. The founder of Polymarket is the youngest billionaire in the world. Alex Danco wrote recently that “prediction is now the entire game. It is the movement and meta-aesthetic that defines our main branch of society going forward.” You can see it in a wide range of cultural gestures: Labubu dolls sold in blind boxes that assign probabilities to which one you might get or sports betting markets that now resemble high-frequency trading terminals. I recently wrote that, in the near future, people are likely to bet on simulations of sports instead of the actual thing — wagering on modeled outcomes of modeled realities. I would also add the growing interest in magic and witchcraft, such as witches for hire on Etsy or the infamous Jezebel article, as examples of Prediction.

More than being a new paradigm, Prediction should be understood in lineage of prophetic soft technologies: technologies that attempt to predict the world not by acting on it directly, but indirectly through code, language, models, or rituals. Hard technologies act on atoms, soft technologies act indirectly, and can be realized in the world of atoms. Language and software are core soft technologies.

In this lineage, we have Giurdano Bruno’s memory palaces from early modernity, attempting to make sense of post-printing world through mnemonics and magic. We also have the failed Cybersyn project from the 1970s, which was an attempt at using cybernetics to make sense of an uncertain, increasingly complex cold war economy.

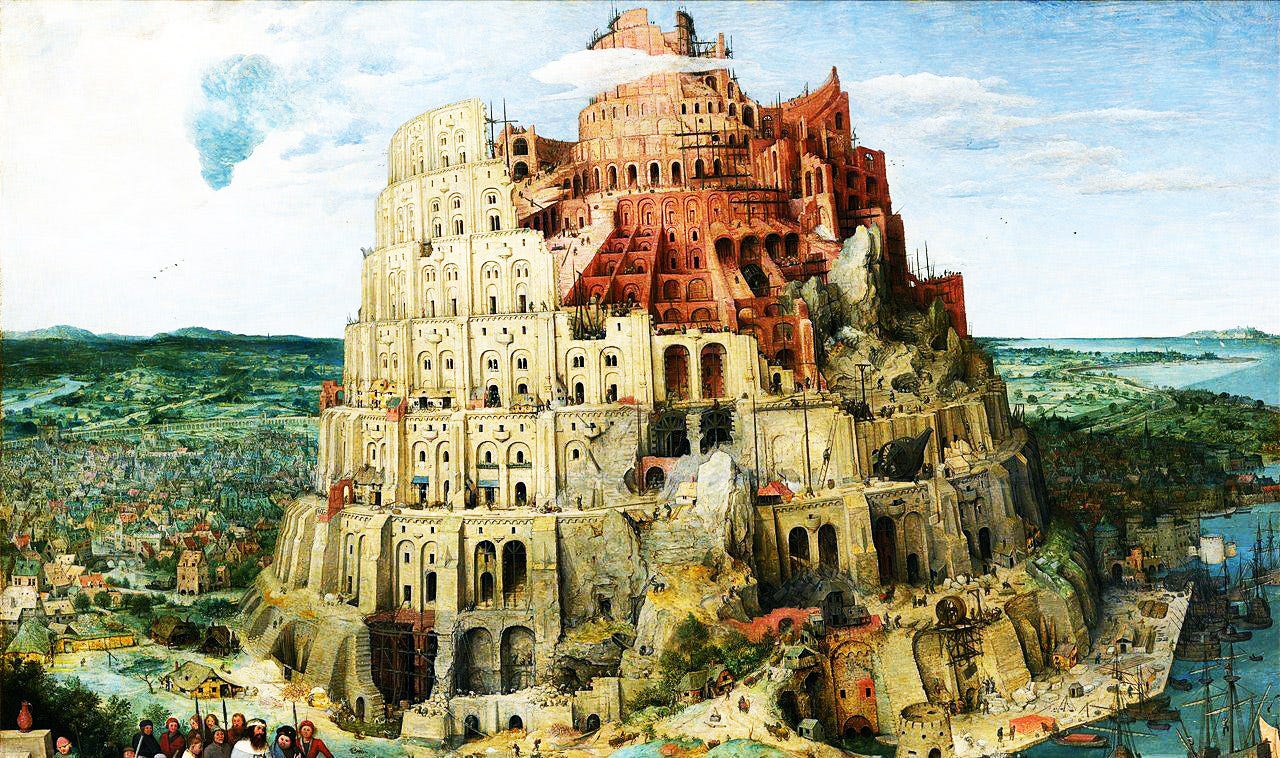

Prophetic soft technologies are liminal. They flourish when predictability breaks down. They boom in moments of epistemic trauma, when our sense of predictability, our confidence that the world obeys familiar patterns, collapses. They are prosthetics for a wounded sense, extensions that help us cope with the loss of a previous temporality.

Giordano Bruno’s Memory Palaces

In the 16th century, Giurdano Bruno lived in a world newly overwhelmed by information. The printing press had made knowledge abundant and externalized. What had once been stored in memory — the rhetorical and moral core of the self — now lived in libraries. Bruno’s response was not to renounce the new technology but to build a parallel one inside the human mind: elaborate mnemonic architectures that could mirror the cosmos and reorder it through imagination.

At its simplest, a memory palace was a method for remembering, but in Giordano Bruno’s hands, it became a full-blown cognitive technology, a symbolic machine for thinking. The technique came from antiquity. Classical orators like Cicero and Quintilian discovered that people remembered information better when it was spatialized. But back then it was mostly used to remember long speeches or memorize long lists.

Bruno inherited this tradition just as the printing press was reshaping what “knowledge” meant. Print made information external, abundant, and fixed. The scholar no longer carried knowledge within; he consulted it. For a thinker raised in the memory-centered humanist world, this was a psychic rupture. The interior cosmos , where intellect and virtue once resided, was being replaced by the library, an external archive that sat outside the human mind.

The memory palace was Bruno’s countermeasure, a cognitive counter-press. Instead of rejecting print, he mirrored it within the mind. Where the printing press gave every reader access to an external memory, Bruno tried to build an internal one: a universe of symbolic architecture that restored agency to the imagination.

In this sense, Bruno’s palaces were a response to print inflicted trauma of seeing human memory displaced by the externalized memory of books. The palace was a symbolic prosthetic, a soft technology for restoring coherence.

Cybersyn

If Giordano Bruno’s memory palace was a prophetic soft technology for the print age, Project Cybersyn was its twentieth-century descendant — a prophetic soft technology for the information age.

When Salvador Allende came to power in Chile in 1970, he inherited the practical challenge of coordinating hundreds of newly nationalized factories and supply chains. Enter Stafford Beer, who proposed to treat the national economy like a living cybernetic organism. His design, Project Cybersyn, would be its nervous system.

Roughly 500 telex machines were installed across Chile. Each night they transmitted data about production, labor, and supply to a mainframe in Santiago. There, Beer’s team processed it using his Viable System Model — a recursive architecture in which every organization mirrors the logic of the whole. At the center sat the Opsroom, a hexagonal control theater lined with screens and molded fiberglass chairs. From this room, policymakers could visualize the pulse of the nation, tracking bottlenecks and adjusting flows

It seemed to work for while. During a 1972 truckers’ strike, Cybersyn’s network helped officials reroute resources and keep essential goods moving. It seemed to prove that a socialist economy could be cybernetic — a real-time internet of production decades ahead of its time.

But the promise was short-lived. Technically, the system was fragile: telex messages arrived hours late, and data was incomplete or falsified. Conceptually, Cybersyn’s central flaw was that it extended the logic of the computer — a closed, rule-bound system — onto an open, deeply human network of conflicting motives. The model assumed the economy would behave like a machine.

When Pinochet’s coup toppled Allende in 1973, soldiers stormed the Opsroom. The fiberglass chairs were photographed as spoils.

Cybersyn’s failure revealed the limits of the computational metaphor. Retrospectively it seems silly that someone thought that you could model intelligence within the system, such as motivations of workers and other inefficiencies. All that Cybersyn showed was that you could pretend to simulate a whole economy until the moment of collapse.

Yearning for a Collapsed Temporality

Writing about the narrative condition post 2016, Venkatesh Rao writes “The world has gotten more complex than we can imagine shared overlays for, and this presents as a persistent weirdness that leaves us with a nostalgia for a shared imagined present that we process into a persistent sense of generalized crisis. But consensus failure is not necessarily a crisis, except to a nostalgic imagination. If you can give up the nostalgia, there is a chance you might find there is no crisis”

Prediction simulates a shared imagined present in the hope that it can recreate a temporality that existed before what Venkat calls the Permaweird took shape (other names for this condition include polycrisis, omnicrisis etc). In this previous temporality, it was possible to predict the direction that the world was going in based on events that happened before. The world operated in what I like to call carnivalized temporality of trends, narrative cycles, memes etc. Prediction tries to replicate this in the aggregate.

Neither Bruno’s memory palaces nor Beer’s cybernetic diagrams were ontologically thick enough to define the ages they belonged to. They were elegant ways of thinking that never hardened into everyday infrastructure. Prediction belongs to the same lineage. It is not the ontology of the present but a symptom — procedural rituals that make us feel as though the world still adds up, even as it slips beyond comprehension.

What Prediction is missing, which stops it from being an entire ontology such as post-modernism or modernism is that there are other ways of being in the world that are non-probabilistic which it does not account for. For example, is Prediction able to model something that is completely novel? Prediction can model linear time but can it model the thick experience of time, something that you would get from reading a book or experiences on the internet that are not browsing social media?

The other giveaway that prediction belongs to a form of reactionary nostalgia, rather than a new ontology, is its pervasive cynicism. The ethos of Prediction is ironic detachment from the future. Participants in meme-coin cycles, sports betting, or prediction markets often don’t act out of conviction that their wagers reveal truth. They act out of recognition that truth no longer matters. They know the game is arbitrary, and the outcomes rigged or recursively generated by the same attention economy that sustains them.

Prediction has an overwhelming amount of cynical participation, and what Peter Sloterdijk once called “enlightened false consciousness”: the ability to see through ideology while still performing it. The wager becomes a parody of belief, a way to inhabit a future one no longer trusts by speculating on its image.

In that sense, Prediction is not the ontology of what comes next but a mourning for the modern ontology of the future as something predictable. Beneath the rhetoric of probabilistic rationality lies a desperate nostalgia for a time when the future could still be believed in.