Work-Hardened Archetypes

Memetic and Mnemonic Archetypes, revisiting sons-of-soil arguments and...Saint Nicholas

This is a note in a series on Archival Time. You can find the rest of the posts in this series here

I grew up in Kochi, on the southern coast of the southern-most state in India, where every December 31st, people gathered on the beach to set fire to a large effigy that looks like Santa Claus. We called it Papanji. I had assumed that it comes from a Portuguese Christmas tradition since Kochi had one of the earliest Portuguese settlements in India, but on the Wikipedia I found connection to the Jewish celebration of the feast of Enoch:

“Some other believes that the myth of Pappanji was originated from the Jewish culture of the coast of Kerala, which has a history of over two thousand years.) The historic Paradesi Synagogue at Mattancherry, near Fort Kochi, records the arrival of Jewish settlers in 70 AD. On the eighth day of the Feast of Enoch, which commemorates the defeat of the Greek army and the recapture of their land, the effigy of the Greek general Bagris is burned after Torah reading. Straw and dry grass are used for making the effigy”

Continuing on this bunny trail, I learned from Santa: A Life by Jeremy Seal that Saint Nicholas was originally Turkish. He has a decidedly un-Christmassy tomb in what is now Turkey. In the late 11th century, sailors from Bari—then under Norman control—robbed the tomb and carried most of his mortal remains back to Italy. (The Venetians later claimed fragments as well) The relics became enormously important, and Bari turned into a major pilgrimage site almost overnight.

The original myth of the saint is closer to the plot of It’s a Wonderful Life. A merchant has gone bankrupt and is contemplating selling his three daughters into prostitution. On the night before he is to give away the first daughter, Saint Nicholas secretly drops a bag of gold coins through the window. He repeats this act three nights in a row, once for each daughter, saving them all. This story establishes Nicholas as a patron of the poor, of gift-giving, and—crucially—of gifts given anonymously and at night.

From there the figure travels north and mutates. In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas becomes Sinterklaas, and elements of older mythologies accrete onto him. From Odin, he inherits the idea of a nocturnal, sky-traveling figure associated with winter and judgment; Odin’s ravens eventually soften into animal companions. From Poseidon, Nicholas retains his role as protector of sailors. This maritime association is not abstract—there are still many churches dedicated to Saint Nicholas along rivers, coasts, and harbors across Europe.

In the 19th century, the figure crosses the Atlantic with Dutch immigrants. In America, amid the century’s fascination with polar exploration and Arctic extremes, Santa acquires a sleigh and reindeer. These details are consolidated in the 1823 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, which effectively standardizes the imagery.

Finally, in the 1930s, Coca-Cola runs a series of advertisements built around the idea that Coke is best drunk chilled—even in winter. Santa appears wearing a bright red suit, warm, genial, and unmistakably corporeal. That visual hardens. The image goes global.

In short, Santa (or Papanji as I grew up calling him) is not the product of a single myth or culture, but an accretion of stories produced by repeated geographic and cultural dislocation. Each migration of the figure—across languages, climates, religions, and economic systems—introduced small misalignments: pagan motifs layered onto Christian hagiography, maritime patronage combined with winter folklore, moral judgment fused with anonymous generosity, and eventually corporate iconography welded onto ancient ritual.

It is precisely this stacking that gives Santa his durability. The figure remembers where he has been. He carries within him the stress of translation, misunderstanding, and reuse. Rather than weakening the archetype, these dislocations pin it in place, making it resistant to simplification or erasure. Santa cannot be reduced without something important breaking.

Santa is therefore what I will call a mnemonic archetype: a figure that persists not by spreading quickly, but by accumulating memory. Mnemonic archetypes survive by thickening over time, embedding themselves in ritual, calendar, and practice. They do this through the process of continuous dislocations.

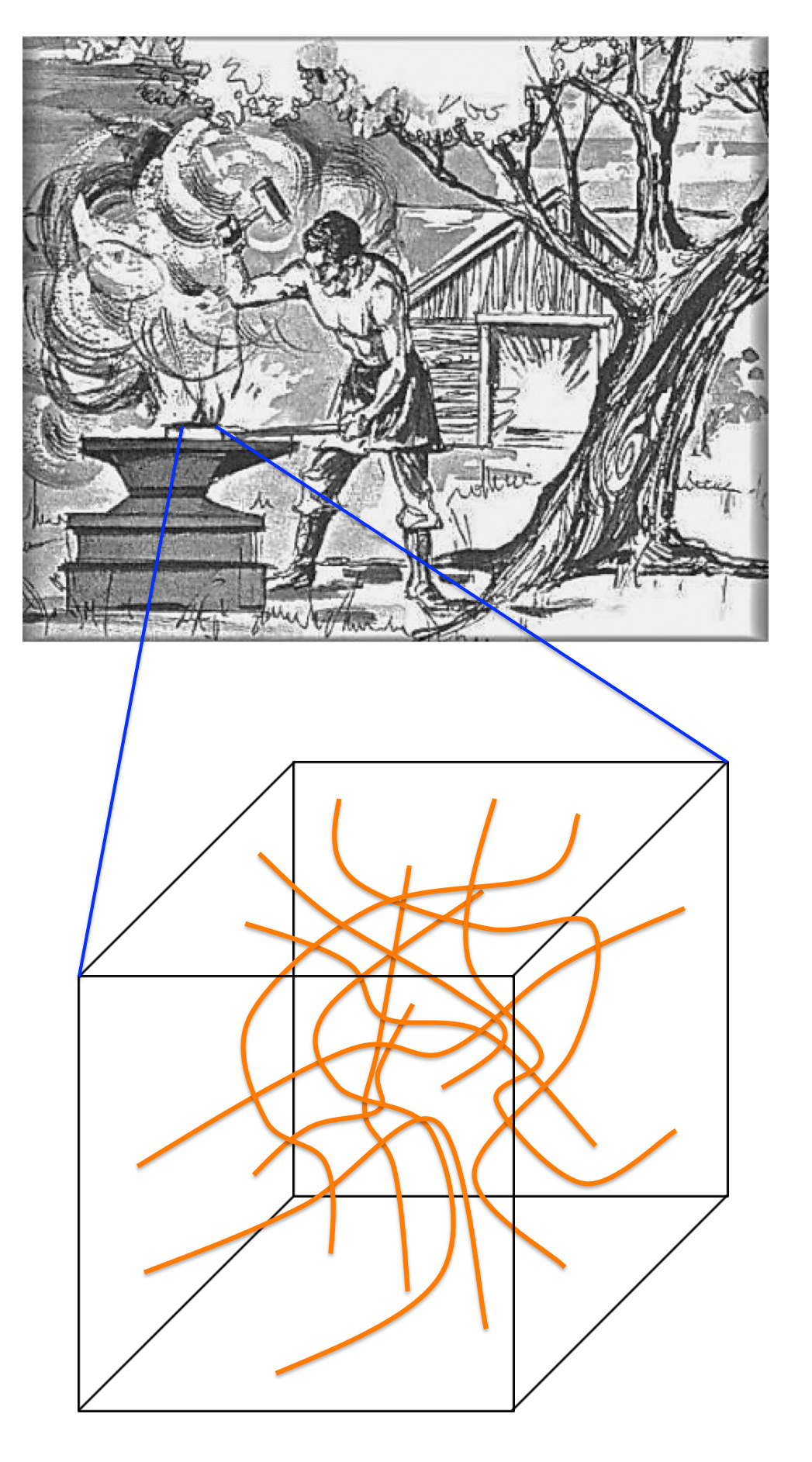

The idea that dislocations provide strength comes from metallurgy, and in particular from the counterintuitive logic of annealing and work hardening. A perfectly ordered crystal lattice is not strong. In fact, it is brittle. When force is applied, entire planes of atoms can slide past one another cleanly, and the material deforms or breaks with surprisingly little resistance.

The insight, as Brian Skinner explains in his Ribbonfarm essay on the physics of swords, is that real strength comes not from eliminating defects, but from multiplying them. Dislocations—misalignments in the atomic lattice—act as points of internal stress. On their own, a single dislocation makes deformation easier: it provides a pathway along which the lattice can slip. But when many dislocations are introduced and forced into proximity, they begin to interfere with one another. They tangle. They pin each other in place. Motion becomes difficult not because the lattice is perfectly aligned, but because it is misaligned in too many incompatible ways at once

Lets look at some other examples of mnemonic archetypes

Dracula: The Immortal That Won’t Settle

Dracula is a character, but he also behaves like a cultural storage device. From his 19th-century crystallization in Stoker’s novel onward, Dracula has accumulated meanings without shedding earlier ones. He is simultaneously aristocrat and parasite, foreign invader and decadent remnant, sexual transgressor and epidemiological threat. Each era reinterprets him—Victorian fears of degeneration, Cold War paranoia, late-modern anxieties about surveillance or immortality—but none manages to close the loop.

King Arthur: The Once and Future Recombination

King Arthur is perhaps the clearest example of a mnemonic archetype produced by historical dislocation. There is no single Arthur. Instead, there is a rolling accretion of figures: Romano-British war leader, Celtic hero, Christian king, chivalric ideal, tragic ruler, national myth. Each retelling claims recovery while actually performing mutation.

Modern historians like Tom Holland have pushed this further, arguing that the Arthurian corpus—especially its emphasis on sacred kingship, just war, and holy relics—was shaped not only by Christian and Celtic sources, but also by contact with Islamic political theology during the medieval period. The Arthurian world emerges not from isolation, but from civilizational adjacency: crusade-era Europe absorbing and misrecognizing ideas of sovereignty, law, and sacred order from its rivals.

What matters here is not whether Arthur “really” came from Islam, Rome, Wales, or nowhere at all. What matters is that the archetype survives because it never stabilizes. Arthur is always lost, always returning, always displaced. Even modern science fiction inherits this structure. Frank Herbert’s Dune is Arthurian in function: a desert king, a chosen figure whose legitimacy is forged through prophecy, exile, and contested sovereignty. The setting changes; the mnemonic load does not.

National Identity as Mnemonic Archetype

Mnemonic archetypes do not exist only in fictional or religious worlds. The world we inhabit has been built, quite literally, through the accretion of archetypes such as Judges, Sovereigns, Saints, and Sinners—roles that persist not because they are efficient or clearly defined, but because they remember. These archetypes stabilize expectations across generations. They encode authority, guilt, legitimacy, mercy, and punishment in forms that resist simplification. Modern institutions did not replace them; they annealed and hardened them through the years.

Perhaps the strongest mnemonic archetype produced by modernity is national identity. National identity is not merely an ideology or a set of beliefs. It is a memory-bearing structure that binds people to territory, ancestry, and imagined continuity. Like Santa or Arthur, it is an accretion: myths of origin layered with selective histories, founding violence layered with redemption narratives, administrative borders layered over older cultural geographies

The sons-of-the-soil paper (which I’ve written about before) is especially revealing about what happens when new identities are introduced into a place that already has several dislocations present. One of the paper’s most counterintuitive findings is that immigrant or settler populations—despite often being poorer, more marginalized, or more directly harmed by the state—are rarely the primary drivers of rebellion. Instead, sustained conflict almost always originates with long-settled populations who see themselves as indigenous to the territory

Immigrants arrive with identities, grievances, and cultural practices of their own, but these identities are comparatively light. They are portable. They can be renegotiated, hybridized, or abandoned if conditions change. Immigrant groups tend to orient toward opportunity, exit, or accommodation rather than existential struggle. Even when they mobilize politically, they do so episodically and rarely sustain long insurgencies.

By contrast, long-settled populations accumulate mnemonic density. Over generations, identity becomes entangled with land itself: burial sites, ancestral villages, irrigation systems, sacred geography, local heroes, remembered betrayals. These are not symbolic attachments in the abstract sense; they are stored memories embedded in territory. The paper shows that when demographic change occurs—especially when it is rapid, state-sponsored, or perceived as permanent—it is interpreted not as policy but as erasure.

This is the critical dislocation. The introduction of new populations does not dilute national identity; it activates it. The presence of outsiders sharpens the remembered boundary between “those who belong here” and “those who do not.” Importantly, this activation is not ideological. The long-settled group does not suddenly adopt a new doctrine or belief system. Instead, existing memories are reinterpreted under threat. What had been background knowledge—stories of origin, prior dispossession, ancestral entitlement—moves to the foreground.

Fearon and Laitin emphasize that these conflicts are especially intractable because the state cannot credibly commit to stopping migration or reversing demographic change

Every new settlement, road, census, or development project becomes evidence that the remembered identity is under existential pressure. This produces a feedback loop: demographic change intensifies mnemonic activation, which provokes resistance, which invites repression, which further deepens memory. The result is not explosive civil war, but long-duration, low-intensity conflict—precisely the pattern the paper documents.

All of this makes national identity legible as a mnemonic archetype. It does not spread only through persuasion or media. It condenses through dislocation. Immigration introduces new identities into a place, but it is the reaction of the place—its stored memory—that generates political force. The conflict persists because what is being defended is not a policy preference but a remembered continuity.

The opposite of Mnemonic Archetypes are Memetic Archetypes.

If mnemonic archetypes persist by accumulating memory, memetic archetypes persist by refusing it. They are not designed to endure across time, but to move rapidly across space. Their primary fitness function is not depth or continuity, but velocity.

Memetic archetypes are deliberately light. They minimize internal contradiction, shed historical context, and externalize interpretation to the audience. Where mnemonic archetypes thicken through dislocation, memetic archetypes actively smooth it away. Anything that slows recognition, demands rehearsal, or requires initiation is treated as friction and selected against.

The clown is an instructive example. Unlike Santa, the clown carries almost no memory. It is instantly legible, culturally portable, and context-indifferent. A clown does not improve with repetition; it resets. Each appearance is meant to be consumed and forgotten. Its function is release, not remembrance.

Memetic archetypes do not fail because they are shallow; they succeed because they are shallow. They thrive in environments where attention is scarce, distribution is cheap, and interpretation must be immediate. Social media platforms, advertising systems, and algorithmic feeds all privilege archetypes that can be recognized without explanation and repeated without consequence.

Crucially, memetic archetypes do not own their protocols. Their rules are supplied by the medium of distribution. Remove the distribution channel and the archetype collapses. Unlike mnemonic archetypes, which can persist locally without circulation, memetic archetypes require constant movement to remain legible.

A pre-modern illustration of this dynamic can be found in Gargantua and Pantagruel by François Rabelais. Rabelais’s books are built almost entirely out of carnival material: scatological humor, grotesque bodies, inversion of authority, mockery of learning, and excess without restraint. They draw on a dense, living substrate of oral culture—marketplace jokes, clerical satire, festive misrule—that was immediately legible to their original audience.

But what gives Rabelais his explosive energy is precisely what makes him hard to translate across time.

The humor depends on shared carnival protocols: familiarity with medieval scholasticism, clerical hierarchies, local dialects, bodily taboos, and rhythms of feast and fast. When those protocols fade, the archetypes lose traction. Modern readers encounter Rabelais not as a living force but as a historical curiosity—brilliant, important, but oddly inert. The jokes land unevenly. The excess feels strained.

This is not because Rabelais lacks depth, but because his archetypes are fundamentally memetic–carnivalesque rather than mnemonic. They are designed for eruption, not endurance. They thrive in circulation and collapse when removed from their original medium of social practice. Unlike Santa or national identity, they do not accumulate dislocations in a way that thickens meaning over time. They burn brightly, then go cold.

This contrast helps clarify the difference between the two regimes. Mnemonic archetypes—saints, sovereigns, nations—can survive radical changes in medium because they store memory internally, in contradiction, ritual, and place. Memetic archetypes, even when canonized as literature, remain dependent on the vitality of the protocols that originally animated them. When those protocols disappear, explanation replaces participation, and the archetype loses force.

Rabelais reminds us that not all powerful cultural forms are meant to last. Some are designed to move through a moment, not to remember it.

This also explains their characteristic failure mode. Memetic archetypes do not decay slowly. They exhaust. Overexposure, irony saturation, or platform shifts strip them of novelty, and without memory to fall back on, they evaporate. Attempts to stabilize them—through branding, institutionalization, or explanation—usually kill them outright by introducing the very friction they were designed to avoid.

In short, memetic archetypes are slip-optimized cultural forms. They move well precisely because they refuse to remember. Where mnemonic archetypes resist motion in order to endure, memetic archetypes resist endurance in order to move.

In the next installment we will look at the archetype that disrupts mnemonic and memetic archetypes (hint: named after a character from the Foundation series), and technologies as annealing agents that incorporate newer memories into a civilization.

I found in Rabelais a funhouse mirror of the political present. If you look past the archaisms, it’s apparent that human nature hasn’t changed a bit in the centuries since he wrote his farce. It’s actually quite disturbing from the perspective of someone who wants to see durable change.