Every time I’ve published something on this newsletter using an LLM, it has taken me more time to write than my normal pieces. At the same time I’m overcome with guilt regarding who actually wrote the piece. I can’t really call myself the author of the piece—how else can I define my involvement? Did it cook it up with a recipe? Who exactly is the author? Am I the modern equivalent of a print setter? I’m not going to call myself a creative. That is for teenagers and grifters.

Fixity and the Author Persona

I’ve been reading Elizabeth Eisenstein’s The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe1, and came away with the impression that the idea of an author as we know it today only emerged after the printing press. Previous to that, people wrote manuscripts that were copied by scribes, and it was taken for granted that the information written down may or may not be preserved; and if it is preserved, it will still be lossy because of changes made by scribes through continuous copying. There were nobles and scholars who wrote things down, and unidentified masses that created folk tales which were transcribed, but the persona of the author did not exist.

The invention of the printing press brought on two changes that created the modern-day author. The first one is a property of printing that Eisenstein calls Fixity. Previous to reading Eisenstein’s work, I was under the impression that the primary contribution of the printing press was dissemination and mechanical reproduction. But that only seems to be part of the story. The printing press introduced standardization such as title pages, indexing contents of a manuscript, and pagination, which helped create more cross-referencing among works of different authors. On this Eisenstein writes:

This sort of spectacular innovation, while deserving close study, should not divert attention from much less conspicuous, more ubiquitous changes. Increasing familiarity with regularly numbered pages, punctuation marks, section breaks, running heads, indexes, and so forth helped to reorder the thought of all readers, whatever their profession or craft. The use of Arabic numbers for pagination suggests how the most inconspicuous innovation could have weighty consequences—in this case, a more accurate indexing, annotation, and cross-referencing resulted. Most studies of printing have, quite rightly, singled out the regular provision of title pages as the most significant new feature associated with the printed book format. How the title page contributed to the cataloguing of books and the bibliographer’s craft scarcely needs to be spelled out. How it contributed to new habits of placing and dating, in general, does, I think, call for further thought.

The combined effect of dissemination and standardization was that information acquired a more fixed nature, something which did not exist in the scribe era. This fixed nature allowed authors and printers to improve how data was collected and create a corpus of common knowledge that could be referenced, modified, and improved upon. This property of print created a more fixed relationship to the past. Here is Eisenstein talking about how some of the first printed atlases (Theatrum by Ortelius) were produced (emphasis mine):

By the simple expedient of being honest with his readers and inviting criticism and suggestions, Ortelius made his Theatrum a sort of cooperative enterprise on an international basis. He received helpful suggestions from far and wide and cartographers stumbled over themselves to send him their latest maps of regions not covered in the Theatrum. The Theatrum was . . . speedily reprinted several times . . . Suggestions for corrections and revisions kept Ortelius and his engravers busy altering plates for new editions . . . Within three years he had acquired so many new maps that he issued a supplement of 17 maps which were afterwards incorporated in the Theatrum. When Ortelius died in 1598 at least 28 editions of the atlas had been published in Latin, Dutch, German, French and Spanish . . . The last edition was published by the House of Plantin in 1612.39...

The second change that printing introduced was what I’ll call the creation of the author persona. This change in itself was brought by two properties of print. The first was that print changed the relationship between the audience and the writer. Stories were often previously transmitted in a one-to-many setting through orators or folk tales, but print introduced a more individuated relationship between author and reader, which led to new forms of writing such as the personal essay, as illustrated by this bit about Montaigne:

As a volatile creature, concerned with trivial events, the author of the Essays contrasted in almost every way with the ideal types conveyed by other books. The latter presented princes, courtiers, councillors, merchants, schoolmasters, husbandmen, and the like in terms which made readers ever more aware, not merely of their shortcomings in their assigned roles, but also of the existence of a solitary singular self, characterized by all the peculiar traits that were unshared by others—traits which had no redeeming social or exemplary functions and hence were deemed to be of no literary worth. By presenting himself, in all modesty, as an atypical individual and by portraying with loving care every one of his peculiarities, Montaigne brought this private self out of hiding, so to speak.

The second property of print that helped create the personality of the author was easy dissemination of the image of the author. One of the absolutely metal anecdotes in the book is about the effect of print on the French Revolution. Previous to the printing press, low-fidelity images of kings and nobles were etched on coins. Print enabled more accurate and recognizable images to be printed, and when currency notes were printed in France during King Louis XVI’s reign, they carried a high-fidelity image of him. These notes, printed by order of the king, helped Frenchmen identify him when he was trying to escape through Varennes.

The ability to print and disseminate high-fidelity images had a different, albeit more peaceful and narcissistic, effect on writers. Before the 15th century, author portraits were continuously copied by different scribes, which eventually blurred and modified the original features of the author, and eventually turned the portraits into the robed, mournful figure that stoicism accounts on Twitter are very fond of. Print, with its standardization of images and dissemination powers, drew writers into a frenzied drive for fame and recognition while seeding the need to be different and unique from others in the same profession. As Eisenstein notes:

When historical figures can be given distinct faces, they also acquire a more distinctive personality. The characteristic individuality of Renaissance masterpieces in comparison with earlier ones is probably related to the new possibility of preserving by duplication the faces, names, birthplaces, and personal histories of the makers of objects of art.

Fixity, Persona and Narrative

I don’t know if there have been any other major changes in authorship since Fixity of information and creation of the author personality were introduced. Perhaps 19th-century copyright law was another big change, but on one hand it seems like an extension of property law, on the other, the major effect of copyright was perhaps that it institutionalized fixity and persona of the author.

When Foucault tries to define an author in his 1967 essay What Is an Author2 (written some twenty years before Eisenstein’s book), he refers to discursiveness—the ability to refer back to an author’s work and form different interpretations of it3—as the main property that defines an author (he uses Freud and Marx as classical examples). This, to me, does not seem that different from fixity and persona of the author.

There have been new mediums, styles, and changes in the tenor of the relationship between the author and the reader, but the properties that have defined authorship have largely remained unchanged.

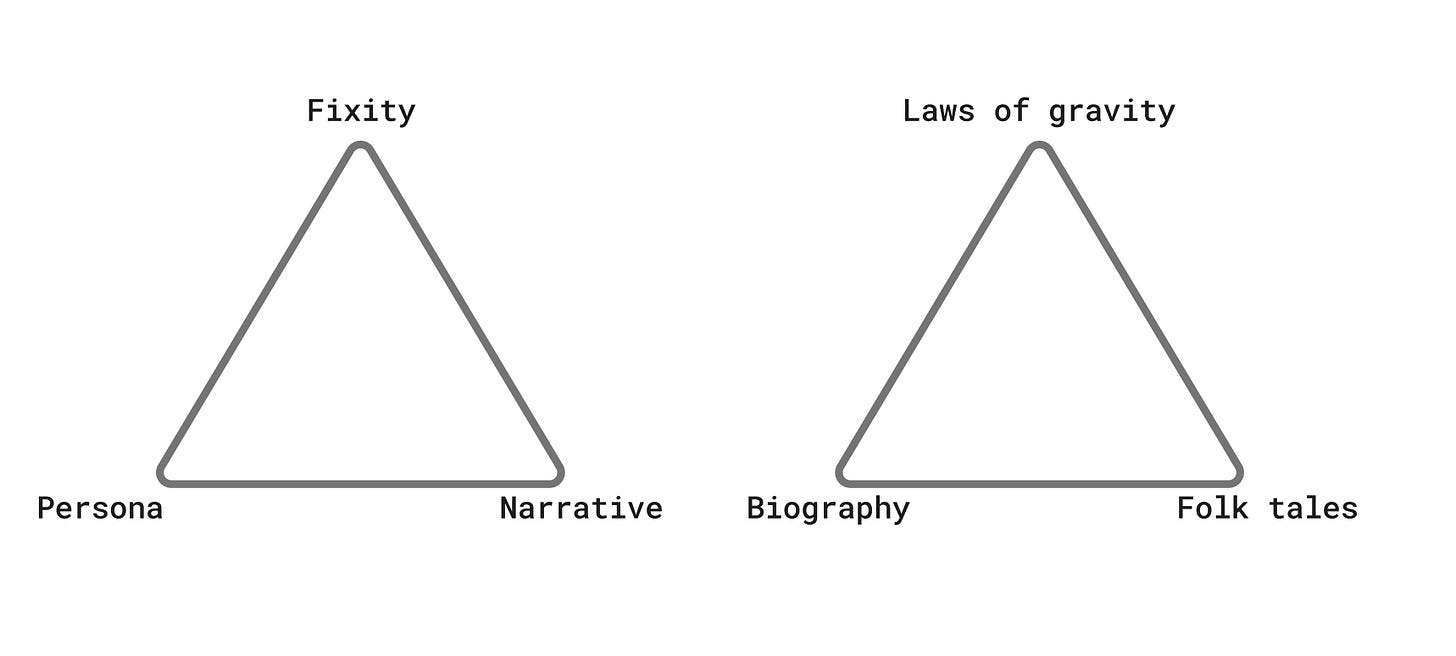

I like to think of authorship as a Spreng’s triangle with Fixity, Persona, and Narrative as the vertices. Narrative is the vertex I’ve not touched on. I think of it as modes of storytelling and writing that have emerged in different mediums. They usually have a medium is the message effect such as the novel not existing before the printing press for example. Different types of authorship can either be pure forms of each vertex or a mix of all three vertices. The pure forms in this case would be scientific knowledge such as laws of gravity, biographies, and older forms of folk tales that don’t always have a single authorship.

To take this exercise further:

Fixity + Persona: Marx, Freud, and other discursive writers, but also self-improvement

Persona + Narrative: If the persona is more intensive, then it is autofiction; if narrative is more intensive, then it’s the novel. Great novels combine all three. I’m reading RedBud by Melville and it is a curious mix of autobiographical information, narrative, and information about sailors in the mid 1800s.

Narrative + Fixity: explainers, history

Lack of permanence

With LLMs, all three vertices are affected. There is less fixity of information because everyone is getting their own divergent version of information from their LLMs4. Narrative perhaps remains the same, but there are potentialities and intensities that could introduce new types of narrative. Of the three, Persona of the author is what is affected the most by LLMs. If you are accessing things written by an author through an LLM interface, which has personalized that information to you based on the context and its memory of you, the idiosyncrasies and personality of the author get lost. The reader goes from an I-thou relationship with the author to a mediated I-it-thou relationship.

I don’t think this change means disappearance of recognizable authors in any way. I like to think of it as analogous to how my relationship with music has changed since streaming services became popular. It used to be that I knew 10–20 artists really well, and those artists defined what music was for me and formed a big part of my teenage identity (unfortunately). With streaming services, I still know 10–20 artists really well at any given time, but there is a large corpus of music that I discover and enjoy without it being a strong part of my identity. Although this fading relevance of authorship in music is something people voice as a criticism, I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing.

There has been an explosion of both writing and music produced in the internet era. When iTunes launched in 2003, there were 200,000 songs available, and by 2012 this number had become 26 million. Now it’s probably in the hundreds of millions. The amount of information produced is several times more exponential for writing because it costs almost nothing to write something and put into the world now. With an explosion of information, it is necessary to change our relationship to the information as well — so that we are not psychically overwhelmed and are able retain our sense of wonder for what might be possible.

Ending with another quote from Eisenstein:

“A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330.”

In the essay Foucault writes: “The distinctive contribution of these authors is that they produced not only their own work, but the possibility and the rules of formation of other texts. In this sense, their role differs entirely from that of a novelist, for example, who is basically never more than the author of his own text. Freud is not simply the author of The Interpretation of Dreams or of Wit and its Relation to the Unconscious and Marx is not simply the author of the Communist Manifesto or Capital: they both established the endless possibility of discourse. Obviously, an easy objection can be made. The author of a novel may be responsible for more than his own text; if he acquires some 'importance' in the literary world, his influence can have significant ramifications. To take a very simple example, one could say that Ann Radcliffe did not simply write The Mysteries of Udolpho and a few other novels, but also made possible the appearance of Gothic Romances at the beginning of the nineteenth century.”

From the essay: “we might call them 'initiators of discursive practices”

Faced with the problem you describe—the dilution of the author’s persona—I’ve developed an approach that restores, in a way, the traditional role of the scribe. I write my thoughts in French, then use an LLM as a personal translator to transpose them into English.

Complex system for a simple problem? Probably. But it lets me lie to myself that the LLM is a technical tool rather than a co-author, removing printing press created guilt about misappropriated authorship and establishing a relationship closer to the era when scribes transmitted without fundamentally altering the original work.

This seems to place me on the Fixity-Persona axis and, with the length of this comment, leaning strongly towards discursion rather than self-help - a nice insight for me to take away.