General-Purpose Technologies as Annealing Agents

Towards a more technology informed theory of social acceleration.

This is an attempt to synthesize several items I wrote under the series Archival Time over the last four months. Reading a few of the earlier pieces is recommended but not necessary.

Technology functions as an annealing agent in culture, temporarily softening cultural material so that new dislocations can be introduced and retained.

A dislocation, as we discussed in Work-Hardened Archetypes, is a memory-bearing mismatch: a form of unresolved tension that is managed by protocols and technology. More on that later. For now, let’s say dislocations are how civilizations remember over the long term. First, a metallurgy refresher.

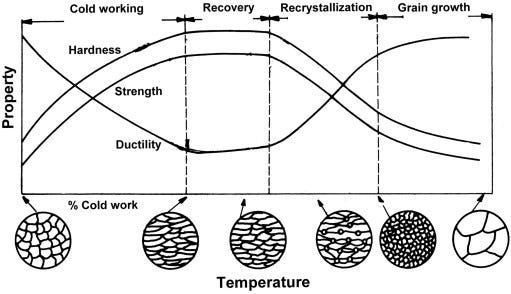

In metallurgy, annealing is used to reduce the stress in work-hardened metal, which has accumulated dislocations either through use or by design (as in the case of sword making). During the recovery stage, the metal is heated to a temperature that relieves internal stress by removing dislocations. Then, during recrystallization, the metal is heated to below its melting point but above the recrystallization temperature so that new grains begin to form, replacing the old deformed grains. During the final stage, the metal undergoes controlled cooling, which enables new grain growth. This final stage completely changes the metal’s microstructure, resulting in more ductility and lower hardness values. Greater ductility allows the metal to handle more stress and also makes it easier to work with.

General-purpose technologies1 have what I’ll call heating and pinning effects.

The heating produced by GPTs mobilizes dislocations that have accumulated under long periods of institutional and social hardening. Institutions, roles, and protocols do not disappear, but they loosen. What we experience as social acceleration is the sensation of a system approaching a structural phase boundary, where rearrangement becomes cheap and established constraints temporarily lose force.

This moment closely resembles what Mikhail Bakhtin called carnival time: a suspension of ordinary hierarchies, norms, and temporalities. In carnival, roles invert, seriousness dissolves, and fixed identities become temporarily mobile, making order—and the new form it takes—renegotiable. Carnival is heat applied briefly and collectively.

Each major general-purpose technology produces a carnival interval.

Consider one of the general-purpose technologies that produced the world machine of the last four hundred years: the printing press.

The printing press heated culture by dramatically lowering the cost and friction of reproducing and disseminating information. Movable type made it possible to produce many identical copies of texts far more quickly and cheaply than hand-copying, which in turn expanded literacy and access to books beyond ecclesiastical and elite circles. Before print, reading was often a collective activity mediated by priests and scribes; texts were copied by hand, subject to variation, and typically encountered in communal or liturgical contexts. After print, readers increasingly encountered texts privately and directly, fostering new reading practices and relationships to scripture, knowledge, and authority. The shift from a priest–audience relationship to an audience–book relationship helped decentralize interpretive authority and underwrote the emergence of individual critical judgment, contributing to broader cultural transformations in the Renaissance, the Reformation, and beyond.

The pinning effect of printing came through the standardization and preservation that Elizabeth Eisenstein called typographical fixity. Unlike manuscripts, which varied with each scribe and could drift or diverge over time, printed texts remained stable across copies and editions, allowing scholars and readers to reference the “same” text reliably. This stability made it possible to compare, critique, and build upon existing works in ways that manuscript culture did not reliably support. One striking historical example is the production of early world atlases such as Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Ortelius solicited maps from contributors across Europe, and successive printed editions incorporated these revisions into a common, standardized corpus that could be widely disseminated, critiqued, and built upon. The result was not only broader distribution but the creation of a shared reference framework for geography and knowledge, accelerating collective scholarly enterprise in ways that earlier manuscript traditions could not sustain.

The internet liquefied distribution and coordination, producing aggregation dynamics that dissolved firm boundaries, professional gatekeeping, and institutional pacing. Publishing, broadcasting, organizing, and mobilizing all became cheap enough to outrun governance. What followed was a carnival interval in the sense articulated by Bakhtin: hierarchies inverted, authority mocked, identities loosened, and collective attention surged in grotesque, cyclical bursts. Anonymous users could dethrone experts; memes could outperform institutions; outrage and humor circulated with equal force.

During this interval, protocols lost binding force faster than new ones could form. Journalistic standards, academic authority, corporate boundaries, and even the distinction between public and private all softened under heat. The resulting sensation of social acceleration came less from linear speed than from temporal suspension: the ordinary rhythms of institutional time were displaced by carnival time—cyclical, excessive, regenerative, and collective.

These phases feel fast because they are out of time. Like carnival, they are lived as exception rather than continuity. But carnival never lasts. Cooling follows. New protocols and technologies pin what survived the heat. The temporal regime produced by pinning is what I’ve been calling Archival Time. If the social web produced carnival time, then LLMs produce archival time.

Contrasting the carnival time of the internet with archival time, we wrote:

If the internet lives in cycles of frenzy and renewal, language models operate in archival slices—frozen cultural moments recombined as if timeless. Each model release creates a new epoch, already slipping toward obsolescence.

And:

LLMs do not impose progressive continuity in the Enlightenment sense. Instead, they create archival temporality: sealed cultural snapshots recombined into a perpetual present.

Each model is an epoch, frozen at a particular training cutoff. GPT-3, GPT-4, GPT-5—each is a total but temporary world, replaced by the next. Unlike carnival temporality (cyclical, regenerative) or official temporality (linear, progressive), LLM temporality is discontinuous, iterative, punctuated. Culture flows around it, non-stationary, but the model remains fixed until retraining. The rhythm is not feast and renewal, nor progress and accumulation, but the periodic release of archival slices of culture.

This means LLMs introduce a temporality that is genuinely new, one that forces us to invent new cultural modes of production. How do we write, create, and remember in an environment where our tools are discontinuous archives, replaced every few years? How do we treat cultural memory when it arrives in frozen epochs, each already obsolete the moment it appears?

Toward a new theory of social acceleration: general-purpose technologies do not permanently accelerate society. They introduce carnival time into historical time—a bounded interval in which accumulated dislocations become mobile, hierarchies loosen, and rearrangement becomes cheap. What is usually described as social acceleration is not simply an increase in speed, but a temporary suspension of ordinary temporal discipline: roles blur, norms invert, authority loses its grip, and coordination outruns governance.

Social acceleration is a phase condition. During these heated intervals, society feels fast because it is out of sync with its own institutions. Old protocols no longer bind, while new ones have not yet hardened. This produces the characteristic sensations of instability, improvisation, excess, and possibility that accompany major technological shifts.

But carnival never lasts. Cooling follows. Dislocations that were briefly free to move are selectively pinned through new protocols, standards, laws, platforms, and institutional forms. What emerges is not a return to the prior order, nor a simple slowing down, but a new archival temporality: a denser social structure that remembers more than what came before. The post-pinning society is slower in some dimensions, faster in others, but above all more complex, layered, and internally differentiated.

Archival temporality can only be produced by technology. In Cozyweb Animals, I wrote about how cozyweb groups are an attempt to regulate the heat produced by the internet using human coordination.

The cozyweb can be understood as a human-scale pinning response to the heating effects of the social web. Where feeds and platforms produce carnival time—flattened simultaneity, identity volatility, perpetual reaction—the cozyweb attempts to cool things down by reintroducing protocol at the interpersonal level. Small groups, private servers, and niche forums substitute constant attunement for formal governance. Shared irony, self-awareness, and cynicism function as stabilizing norms. The cozyweb does not restore grand narrative or authority; it offers affective regulation through mutual presence.

But this solution carries a hidden cost. Because the cozyweb lacks external pinning mechanisms—law, hierarchy, durable institutions—it must be continuously reenacted to hold together. Attunement lacks long-term memory and must be constantly performed. Cynicism cannot harden into doctrine; it must be refreshed through memes, in-jokes, and repetition. As a result, the cozyweb risks reproducing the very carnival temporality it is trying to escape. The tempo required to maintain equilibrium becomes exhausting, and what begins as cooling turns into a slower, more intimate form of heat. Without archival pinning—without protocols that can remember on behalf of participants—the cozyweb remains suspended in a fragile in-between state: neither the acceleration of the feed nor the solidity of institutions, but a perpetual micro-carnival sustained by constant maintenance.

Seen through the lens of technology as heating and pinning agents, culture does not accelerate in a straight line. Each general-purpose technology introduces a carnival interval, followed by a phase of consolidation in which complexity accumulates. The feeling of endless acceleration is the feeling of living inside repeated heating cycles, mistaking phase transitions for permanent velocity.

***

Some LLM Fermi Estimates of Heating required for Technological Regimes

One further implication of thinking about technology as an annealing agent is that as social life becomes more complex and more densely pinned, it takes more delivered energy for technology to produce a comparable heating effect. This is not because complex societies are inert or resistant in some absolute sense—work-hardened metals, after all, store enormous internal strain—but because the heat must be applied everywhere, continuously, and at sufficient intensity to overcome an increasingly fine-grained lattice of protocols, roles, and institutional memory.

Early general-purpose technologies achieved cultural heating with surprisingly little physical energy because they operated as high-leverage amplifiers riding on existing human and biological systems. The printing press is the clearest example. A rough Fermi estimate makes the contrast visible. Even generous historical estimates suggest that the total number of books produced in Europe over the first century and a half of print runs into the hundreds of millions. If we assume an average book mass of roughly half a kilogram and an energy intensity for paper production on the order of tens of megajoules per kilogram, the total embodied energy of early print culture lands on the order of 10¹⁵ joules, or roughly one terawatt-hour, spread over decades. Even multiplying this estimate several times to account for transport, presses, and inefficiencies still leaves printing’s cultural heating operating in the range of single-digit terawatt-hours over a century. The effect was enormous, but the furnace was small: localized mechanical power, human labor, biomass, and slow diffusion were sufficient to soften interpretive authority and mobilize dislocations embedded in medieval institutions.

The internet represents a qualitative shift. Here, heating is no longer episodic or local but continuous, global, and synchronous. The substrate that liquefies distribution and coordination—fiber-optic cables, cellular networks, routers, data centers—must be powered at all times. A comparable Fermi pass immediately yields numbers several orders of magnitude larger. Contemporary estimates place global data center electricity consumption alone in the hundreds of terawatt-hours per year, with transmission networks adding hundreds more. Unlike print, this is not cumulative energy spread thinly over generations; it is a standing burn. Cultural heating in the internet era is maintained by an always-on infrastructure that keeps society perpetually near a phase boundary, sustaining carnival time rather than merely triggering it.

Large language models push this dynamic further. LLMs are not merely content multipliers; they are archival furnaces that must continuously recompute, serve, and refresh frozen cultural snapshots at planetary scale. Even conservative Fermi estimates show why their temporal effects feel different. A single model query consumes only a fraction of a watt-hour, but multiplied by billions of interactions per day, across training runs that themselves consume tens or hundreds of gigawatt-hours, the energy budget quickly climbs into tens to hundreds of terawatt-hours annually, layered on top of an already energy-intensive internet substrate. Here, heating is no longer about mobilizing discourse alone; it is about maintaining vast, discontinuous archives in active circulation, keeping cultural memory simultaneously frozen and accessible.

The pattern that emerges is not linear acceleration but escalating energetic density per unit of cultural rearrangement. Printing softened society with minimal heat because institutions were coarse-grained and sparsely pinned. The internet required vastly more energy to dissolve boundaries because it had to reach deeper into everyday coordination. LLMs require more still, not to accelerate society in the carnival sense, but to sustain archival temporality—a regime in which cultural memory itself becomes infrastructural, expensive, and discontinuous.

Seen this way, the feeling that technological change now “costs more” is not an illusion. As civilization accretes protocols, standards, and memory, heating can no longer be applied in bursts; it must be distributed, personalized, and permanent. The furnace grows not because society is harder to move, but because it remembers more.

Using this definition of General Purpose Technologies: General-purpose technologies (GPTs) are technologies that can affect an entire economy (usually at a national or global level).[1][2][3] GPTs have the potential to drastically alter societies through their impact on pre-existing economic and social structures. The archetypal examples of GPTs are the steam engine, electricity, and information technology. Other examples include the railroad, interchangeable parts, electronics, material handling, mechanization, control theory (automation), the automobile, the computer, the Internet, medicine, and artificial intelligence, in particular generative pre-trained transformers.

I wonder about a Carnot efficiency metaphor, where the work you get is (1-Tc/Th). The culture you’re operating in sets the Tc, the technology sets Th. In the long run, the machine heats its environment and stops being an effective way to turn heat into energy. When Luther’s theses hit the wall, Tc is way below the Th of the printing press. The press runs and runs, society heats up, and eventually Tc approaches Th, and the printing press stops being effective at turning energy into work (and postmodernism is people noticing this).

It’s quite a detour from the metallurgical analogies you’ve been building. But I’m now pretty curious about how you would define the temperature of a civilization. The phase transition metaphor clearly works, but there’s also something about 1950s American capitalism that (independent of phase) seems “high temperature”, like it’s going to spread irresistibly until the whole world reaches that temperature, and a big question is if China and the US are really the same material but started at different T0 and with access different energy sources, or if they’re fundamentally different (metal vs ceramic) and why.

Fwiw, I took an unsatisfying crack at defining temperature here: https://claude.ai/share/6ca0b59a-fa14-4b53-a75a-cb60fec85b7c

And a slightly more satisfying crack at reconciling work hardening / Carnot / exotic temperature definitions here: https://chatgpt.com/share/69633fa8-e30c-8008-b872-d3fb3d6242ef

Temperature related or not, I’m very excited to see where you go next!!