Thermal Memory

How technological memory affects different layers of civilization

This is a note in a series on Archival Time. You can find the rest of the posts in this series here

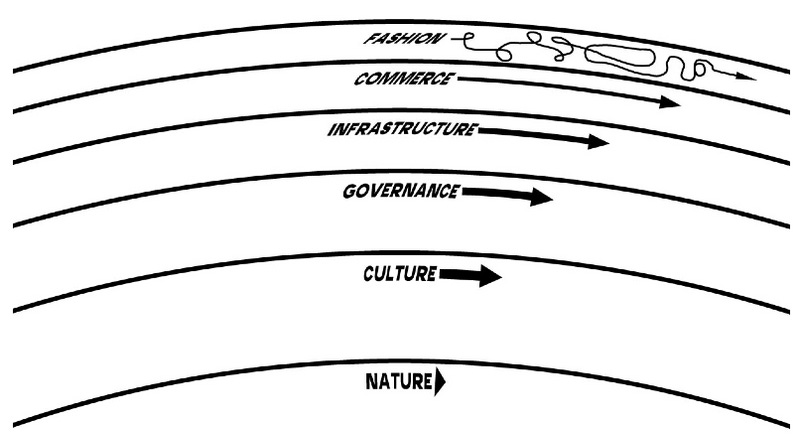

Stewart Brand’s Pace Layers model describes how different strata of civilization move at different speeds. In Brand’s words:

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

All durable dynamic systems have this sort of structure. It is what makes them adaptable and robust.

The core insight of the model lies in the relationship between the layers: the slippage between them allows shocks to be absorbed rather than transmitted wholesale through the system. When a financial crisis hits commerce, governance has time to respond before culture is destabilized. When a new technology disrupts fashion, infrastructure has time to adapt before nature is scarred. The different speeds create a kind of civilizational shock absorber.

Brand introduced pace layering first as a theory of buildings in How Buildings Learn (1994), then expanded it to civilization in The Clock of the Long Now (1999). What the model does not capture—and perhaps could not have captured in 1999—is how the different layers store memory, and what happens when a new technology transforms the memory capacity of the entire stack at once.

This is not a criticism of Brand. In 1999, Moore’s Law was well understood as a phenomenon of chip density, but its cultural effects were just beginning to manifest. The World Wide Web was ten years old. The smartphone did not exist. The modern concept of the Anthropocene—the idea that human activity had become a geological force—was still crystallizing. Brand was writing about time and responsibility at precisely the moment when both were about to be transformed by technologies of memory that he could not have anticipated in their full scope.

Every general-purpose technology1 produces new types of memory.

The printing press produced durable written texts and, crucially, the fixity2 of information. Before print, manuscripts drifted with each scribe—errors accumulated, versions multiplied, texts got improvised. Print froze information in place. This created new possibilities for cumulative knowledge. Science as we know it depends on this fixity: you cannot build on previous findings if the findings are not fixed for a meaningful duration.

Electricity produced the ability to record sounds and images. But electricity also made available cheaper persistence of light. More hours of the day became available for the creation and consumption of memory-objects.

The internet and Moore’s Law produced memory that is both ephemeral and permanent, auto-saved without conscious effort, cheap enough to be taken for granted. The default is now persistence.

This transformation of memory affects all layers of the pace layers, not just the fast ones. The effects propagate both up and down the stack.

Consider fashion, the fastest layer. Before digital memory, fashion left traces in the historical record, but the granularity was coarse. We know roughly what trends existed in 1890 or 1950 because of photographs, advertisements, and surviving texts. But the micro-fluctuations—the trends that lasted weeks rather than years—left minimal forensic marks. They happened and vanished.

Now consider the microtrends of the internet era. A particular aesthetic emerges on social media, spreads for six weeks, gets adopted/criticized, and dies or becomes forensic material for a different trend in the future. In the age of print, such a phenomenon would leave almost no trace. In the age of early electronic media, it might appear briefly on television and then disappear into the archives. In the age of digital memory, every instance is documented, timestamped, commented upon, analyzed, satirized, and preserved. The microtrend leaves a richer archive than major fashion movements of previous eras.

At the infrastructural layer, new memory technologies produce new protocols. Building codes evolve to incorporate lessons from failures but now the lessons are recorded in richer detail. Safety regulations accumulate knowledge from incident reports that are more comprehensive. Engineering techniques are preserved in databases and tutorials rather than guild knowledge and apprenticeships. The infrastructure layer’s memory becomes more explicit, more searchable, more transferable. At the same time, tacit knowledge becomes harder to attain because the archive layer has become extremely complex for a single person to be trained on.

At the cultural layer, something stranger happens. Culture is supposed to be the repository of implicit memory—the accumulated wisdom that is transmitted through practice rather than explicit instruction. But when explicit memory becomes cheap, the relationship between culture and its documentation changes. Cultural practices that previously existed in the space between generations—transmitted through imitation, absorbed through participation—now exist alongside their own documentation. You can learn a traditional craft from YouTube or use an LLM to learn a new topic. This does not eliminate the tacit dimension, but it changes the ecology in which tacit knowledge develops.

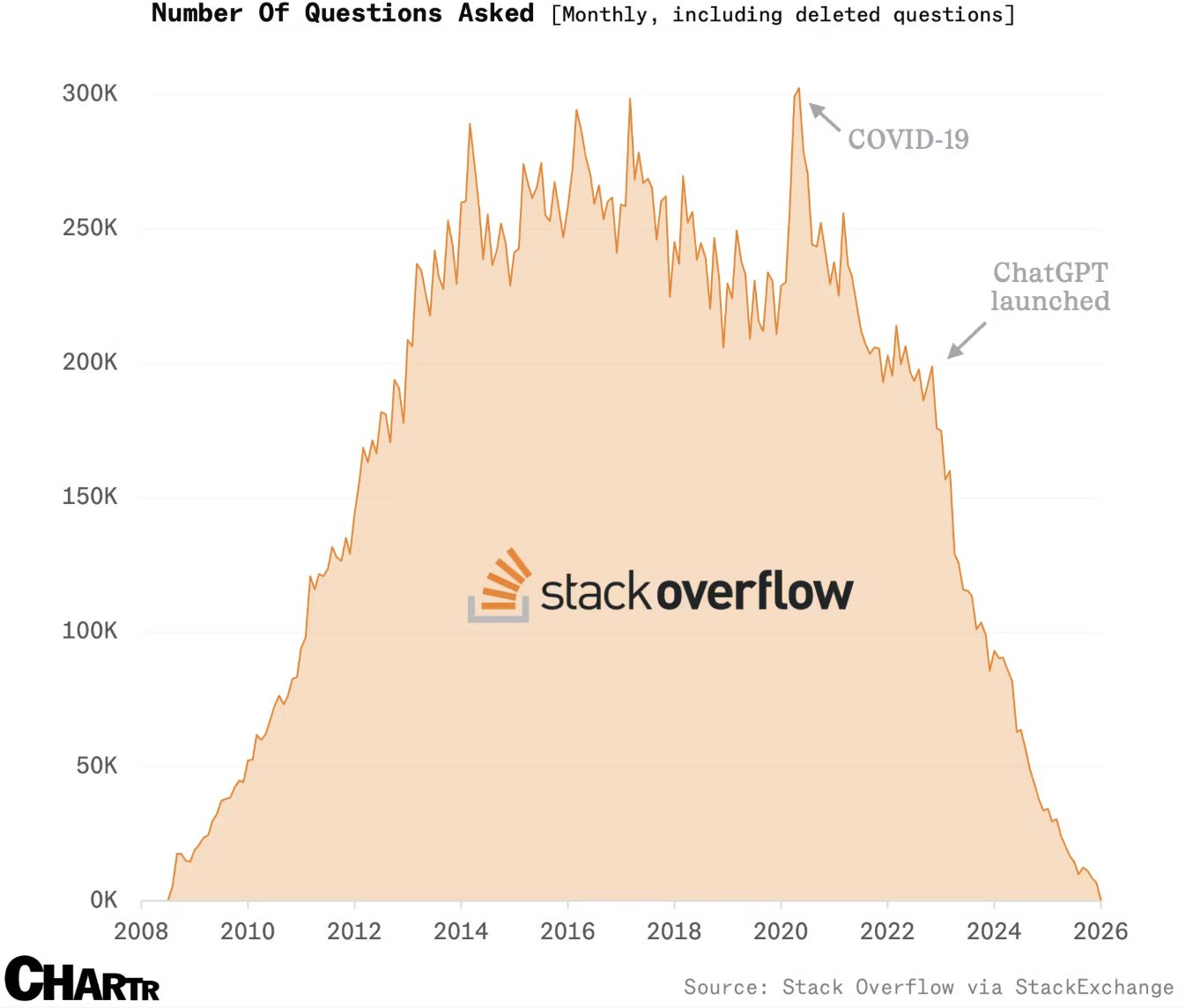

Stack Overflow offers a stark illustration. From 2008 to 2020, the site accumulated millions of questions and answers about programming—a vast externalization of craft knowledge that had previously lived in the heads of experienced developers and was transmitted through code review, pair programming, and apprenticeship. The questions peaked around 300,000 per month during COVID, when a wave of new programmers entered the field. Then ChatGPT launched in late 2022, and the curve collapsed. By 2025, monthly questions had fallen to a fraction of their peak.

The large language models that replaced Stack Overflow were trained on …. Stack Overflow. The cultural memory that the platform externalized became the training data for a technology that made the platform obsolete. The community that produced the knowledge is no longer producing it at the same rate, because the knowledge is now accessible through a different interface. But the models cannot update themselves with new questions that are never asked. The feedback loop that generated the memory has been broken.

One way of thinking about the Anthropocene is that it represents the memory scarring left on nature by technology.

As Vaclav Smil insists, civilization must be understood as an energy-conversion regime, and fossil fuels are its most consequential substrate. The carbon we are releasing today was fixed by photosynthesis over hundreds of millions of years, compressed and stored as coal, oil, and gas through geological time. In Smil’s terms, this is ancient solar energy, accumulated slowly under conditions that no longer exist.

Industrial society is now liberating that energy at a rate that dwarfs natural cycles. Humanity currently consumes on the order of 600 exajoules of primary energy per year, the majority still fossil-derived. This corresponds to carbon flows so large that they overwhelm the Earth’s short-term buffering mechanisms—oceans, soils, and vegetation—which evolved to handle fluxes spread across millennia, not centuries. What took nature eons to sequester, we oxidize in decades.

Smil’s key contribution is to show that this is not an abstract moral problem but a problem of scale and irreversibility. Fossil fuels are not just burned for electricity; they are structurally embedded in fertilizer production, cement, steel, plastics, and global logistics. Because they sit at the base of material throughput, their combustion produces a signal that propagates everywhere: atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, ocean chemistry, biospheric stress, and ultimately the stratigraphic record itself.

The consequence is that our activity becomes geologically legible. Ice cores will register abrupt isotopic shifts; sediment layers will record anomalous carbon signatures, microplastics, and ash horizons. In Smil’s archival sense, this is a persistent inscription—a layer written into Earth’s memory. We are authoring anthropocene by collapsing deep time into industrial time, releasing stored planetary memory faster than the planet can meaningfully reabsorb or forget it.

Here we can introduce a thermodynamic perspective. Memory production requires heat dissipation. This is not strictly metaphor: Landauer’s principle establishes that erasing a bit of information requires a minimum expenditure of energy, released as heat. The principle has a converse implication: creating and maintaining memory also has thermodynamic costs.

A new general-purpose technology introduces new types of memory. In the transition period, some older forms of memory disappear or degrade while the new technology figures out how to remember. Manuscripts are lost before they are digitized. Analog formats become unplayable before they are transferred. There is an overall heating effect as the memory ecology reorganizes.

Think of it as annealing. In metallurgy, annealing involves heating a material and then cooling it slowly to relieve internal stresses and create a more stable crystalline structure. The heating phase disrupts existing arrangements. The cooling phase allows new, more durable arrangements to form. The resulting material is “work-hardened”—it has memory of the stresses it has undergone built into its structure.

Technology anneals each layer of the pace layers. The introduction of a new memory technology heats up a layer—disrupts existing patterns, creates instability, generates entropy. During the cooling phase, new types of work-hardened memories are produced. The layer stabilizes around new arrangements that incorporate the new technology.

But the layers do not anneal at the same rate, and this is where the pace layer framework becomes essential.

In the faster-moving layers—fashion, commerce—you see memory produced all at once, in great quantities, while older forms of memory are erased. Social media generates vast archives of microtrends while the institutional memory of previous retail arrangements is lost. Some of the new memories harden over time: the documentation of this era will be rich in certain dimensions. But much of it remains hot, unstable, subject to platform collapse or format obsolescence.

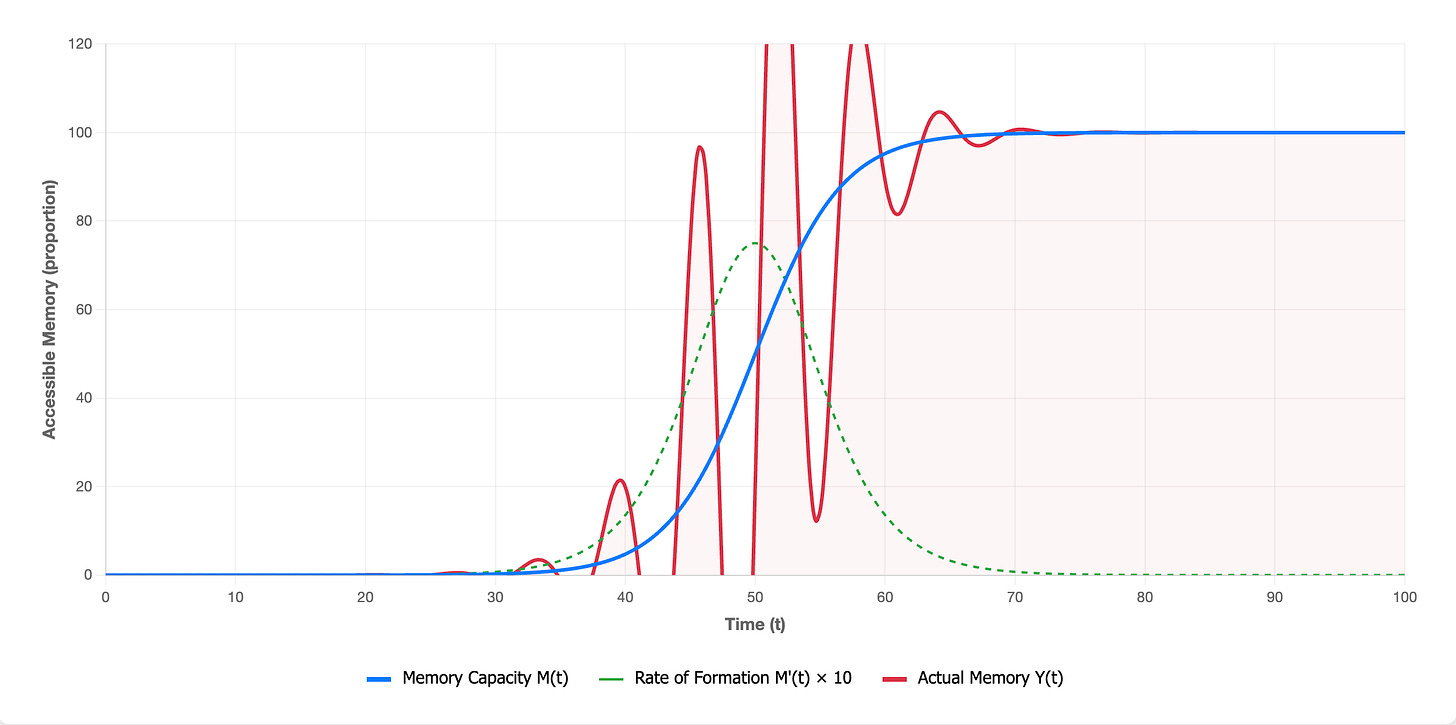

The thermal signature of fast layers looks like a dampened sine curve: rapid oscillations of heating and cooling, intense at first, gradually settling toward a new equilibrium. Each new platform or technology creates a spike of memory production and memory loss, followed by stabilization, followed by the next disruption.

In the slower layers—governance, culture, nature—the pattern is different. Memory accumulates slowly at first. Then, when the new technology finally penetrates to that level, the change is sudden and dramatic. The slow layers have more inertia, more resistance to change. They require more energy for annealing because they store more hardened memories, more accumulated structure. But once the heating begins, the reorganization is profound.

The thermal signature of slow layers looks like an adoption S-curve—or, more precisely, like the heat-versus-crystallization graph in metallurgical annealing. A long plateau of minimal change, then a rapid phase transition, then a new plateau. The slow layers do not oscillate; they undergo state changes.

This framework suggests a distinction between two modes of temporal experience that each produce different types of memory.

Carnival time is the time of the fast layers. It is characterized by rapid turnover, abundant documentation, ephemeral intensity. In carnival time, everything is recorded but nothing necessarily persists. The archive is vast and searchable but thin—a million photographs, each capturing a moment, none capturing a structure. Carnival time produces memory that is broad but shallow.

Archival time is the time of the slow layers. It is characterized by selective preservation, institutional curation, deliberate hardening of memory into durable form. In archival time, less is recorded but what is recorded is meant to last. The archive is smaller but denser—each item the result of a decision that this, and not something else, deserves to be remembered. Archival time produces memory that is narrow but deep.

The tension between carnival time and archival time is not new. Every era has had its ephemera and its monuments. But the digital transformation of memory has radically shifted the balance. We now live in an era of near-total carnival documentation overlaid on archival structures that are struggling to adapt. The boundary between what deserves preservation and what will simply be preserved by default has become unclear.

The memory ecology of the pace layers is being transformed. Fast layers are generating memory at unprecedented rates. Slow layers are being heated by technologies they did not evolve to absorb. The annealing process is underway. What kind of work-hardened memories will emerge—what structures will survive the cooling—remains to be seen.

What we can say is that the relationship between the layers has changed. Brand observed that fast learns and slow remembers. But when fast can also remember—when the documentation of fashion and commerce becomes as durable as the documentation of governance and culture—then the division of labor between the layers shifts. The slow layers no longer have a monopoly on memory. They retain their monopoly on stability, on absorbed experience, on wisdom. But the memory function is now distributed throughout the stack in ways that the pace layers model did not anticipate.

The question for civilizational health is whether the shock absorption still works. If all layers are remembering everything, can they still operate at different speeds? If memory propagates instantly across the stack, can the slippage between layers still protect against systemic fragility? The answer is not yet clear.

LLM Fermi Estimation

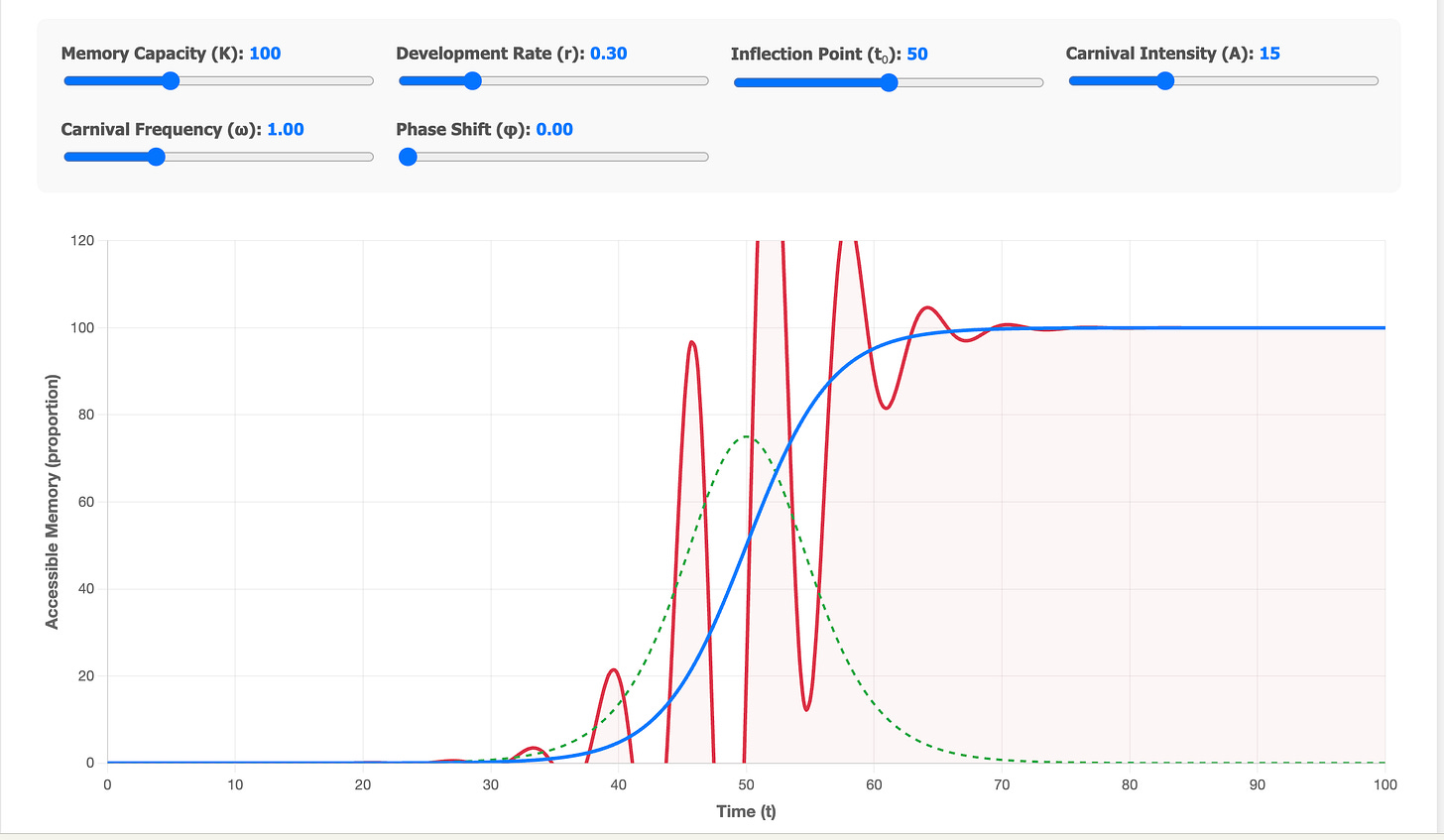

You can play with the graph here

The relationship between archival and carnival memory can be modeled mathematically. Let M(t) represent the baseline accessible memory over time, following a logistic S-curve: M(t) = K/(1 + e^(-r(t-t₀))). This captures how the proportion of history that’s accessible to a civilization grows slowly at first, accelerates through an inflection point at t₀, then approaches a carrying capacity K as it saturates.

But accessible memory doesn’t grow smoothly. During periods of rapid transformation, what’s remembered and forgotten becomes volatile. This volatility can be modeled as carnival oscillations C(t) = A·M’(t)·sin(ωt + φ), where M’(t) is the derivative of the S-curve—the rate at which new memory is being encoded. The key insight is that carnival intensity scales with this rate of change. When M’(t) peaks at the inflection point, the carnival effect is largest: more of the past becomes temporarily salient or suppressed, accessibility oscillates wildly. During stable periods at the beginning and end of the curve when M’(t) is low, these oscillations dampen to nearly nothing.

The total accessible memory at any moment is Y(t) = M(t) + C(t)—the baseline plus the carnival fluctuations. This means that at the very moment when a civilization is transforming fastest, when it’s encoding new memories most rapidly, the accessibility of existing memory becomes most unstable. What was central yesterday becomes forgotten today; what was marginal resurfaces with unexpected force. The system is hot, searching, volatile. Only as the rate of change slows does memory accessibility stabilize again, locking into new patterns that will persist until the next transformation.

This model suggests something counterintuitive: the periods when we’re creating the most new memory are also the periods when we have the least stable access to old memory. Maximum creation coincides with maximum volatility in accessibility.

***

Thanks to my friends at Yak Collective and rafa for discussions that led to this post.

General Purpose Technology: General-purpose technologies (GPTs) are technologies that can affect an entire economy (usually at a national or global level). GPTs have the potential to drastically alter societies through their impact on pre-existing economic and social structures. The archetypal examples of GPTs are the steam engine, electricity, and information technology. Other examples include the railroad, interchangeable parts, electronics, material handling, mechanization, control theory (automation), the automobile, the computer, the Internet, medicine, and artificial intelligence, in particular generative pre-trained transformers.

From Elizabeth Eisenstein’s book Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. I wrote about it previously: The combined effect of dissemination and standardization was that information acquired a more fixed nature, something which did not exist in the scribe era. This fixed nature allowed authors and printers to improve how data was collected and create a corpus of common knowledge that could be referenced, modified, and improved upon. This property of print created a more fixed relationship to the past.

this was amazing

The Stack Ovreflow example is brillaint because it shows how the same memory that enables a tool can also disable the system that created it. Once LLMs consumed all that tacit knoweldge as training data, the incentive to document new edge cases basically vanished. I've noticed this in my own work too, people default to asking an LLM instead of writing down solutions that could compound over time.